Seeds of Rebellion: Reclaiming Education from the Machinery of Collapse

In a world spiraling toward ecological collapse, social disintegration, and spiritual desolation — the so-called polycrisis — it is not enough to politely critique the education system. We must name it for what it has become: an instrument of control, a conveyor belt feeding children into the engines of capitalist consumption, severed from nature, selfhood, and authentic community.

The sterile rituals of modern schooling — the bell, the desk, the standardized test — are not neutral. They are tools of dispossession, carefully engineered to strip children of their innate curiosity, their love for the wild world, and their impulse toward freedom. Education has been colonized. And the consequences bleed into every corner of the crumbling world we now inhabit.

Across history, many thinkers — both Western and Eastern — have raised profound critiques of the way education alienates human beings from their true nature. In this article, we turn our attention to some of the towering voices from the Western tradition — Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Ivan Illich, John Holt, Paulo Freire, Maria Montessori, and Rudolf Steiner — who, across centuries, recognized the silent war being waged against the human spirit in the name of “learning.” Each, in their own way, offered not only a withering critique of the factory-school model but also a luminous vision for what education could be: an act of liberation, a return to life. They looked at education through differing lenses of psychology, sociology, politics, environment and spirituality, critiquing and suggesting alternate modes of education.

Their words are not merely historical curiosities. Today, they burn with a ferocity we can no longer afford to ignore. Let us walk with them now — through their warnings, their visions, and their urgent call to reclaim education before it is too late.

Rousseau’s Cry: The Child Torn from Nature’s Breast

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his seminal work Emile, or On Education (1762), cried out against the brutal disfigurement of the natural child by society’s cold, mechanical hands.

“Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man.”

Rousseau saw formal education as a machinery designed not to nurture but to domesticate — to twist the free growth of the child into the cramped patterns demanded by a corrupt civilization. He declared that the true educator’s task was to protect the child’s natural goodness rather than to “improve” it.

“Plants are shaped by cultivation and men by education… If a man were born in a desert and kept away from all society, he would be perfectly complete in his being.”

For Rousseau, the natural world was the true curriculum. He emphasized education through direct experience: not abstract lessons, but living in nature, feeling its rhythms, learning by doing.

The modern classroom, insulated from earth, wind, and rain, would have appeared to Rousseau as a prison for the soul. He warned that when education forgets its roots in the natural order, it breeds humans who are alienated from themselves, each other, and the living Earth — a prophecy we now see unfolding on a planetary scale.

Illich’s Rage: Dismantling the Schooling Cathedral

Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society (1971) remains one of the fiercest assaults ever launched against the institution of schooling. For Illich, modern education was not a noble project gone wrong — it was a fundamentally corrupt system from the beginning.

“School has become the world religion of the modernized proletariat, and makes futile promises of salvation to the poor of the technological age.”

Illich saw schooling as the ideological arm of capitalism — a machine manufacturing endless needs for certifications, credentials, and validation, ensuring lifelong dependence on systems of control.

“The pupil is thereby ‘schooled’ to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new.”

He envisioned a radically different society — one where learning webs allowed knowledge to flow freely without centralized control; where skills could be shared organically, peer-to-peer, community-to-community.

Importantly, Illich connected education’s corruption to the wider destruction of ecological and communal life. Industrial schooling mirrored industrial agriculture and industrial medicine — all operating on the same model of disempowerment, monopoly, and hidden violence.

Today, Illich’s vision rings not merely radical, but prophetic — a glimpse into the survival strategies we must now urgently reclaim.

Holt’s Plea: Trust the Wild Intelligence Within

John Holt’s heartbreak with education was quiet, personal — but no less revolutionary. In How Children Fail (1964) and Freedom and Beyond (1972), he chronicled how children — born brimming with curiosity — are systematically taught to distrust themselves.

“Children learn from experience that they cannot be trusted to learn on their own.”

Holt described modern schooling as a cult of fear: fear of making mistakes, fear of disapproval, fear of failure. Through grades, tests, and competition, children internalize the belief that learning is dangerous unless sanctioned by an authority.

Yet Holt witnessed again and again how children, left free, learned with astonishing depth and speed. He called for unschooling: trusting the child’s inner guide, removing coercive structures, allowing learning to emerge naturally from life itself.

“Learning is not the product of teaching. Learning is the product of the activity of learners.”

Holt insisted that children, like young animals, needed freedom to roam, explore, and shape their own minds. His vision, deeply respectful of the rhythms of nature, offers a profound antidote to the sterile programming of capitalist schooling.

Freire’s Revolt: Awakening the Consciousness of the Oppressed

Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator and philosopher, saw schooling not just as broken, but as an active agent of oppression. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), he wrote:

“Education as the practice of freedom — as opposed to education as the practice of domination — denies that man is abstract, isolated, independent, and unattached to the world.”

Freire’s banking model of education — where students are treated as empty vessels to be filled — revealed the subtle violence embedded in modern schooling. Knowledge was deposited, not discovered. Authority was absolute, and students were conditioned into passivity.

Freire demanded an education that was dialogical, critical, and political — where students and teachers co-created meaning, questioned structures, and imagined liberation.

“The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach.”

His vision placed education at the heart of revolutionary change.

Until people could reclaim their own voice, their own power to name the world, no real transformation — personal or societal — was possible.

Freire’s pedagogy was not a classroom technique. It was a call to arms.

Montessori’s Cultivation: The Architecture of Freedom

Maria Montessori’s genius lay in understanding freedom and discipline not as opposites, but as two sides of the same sacred coin.

In The Secret of Childhood (1936) and The Absorbent Mind (1949), she emphasized that the child is a builder of himself, driven by inner developmental laws. The educator’s role was to prepare the environment, then step back and allow the child to construct his own being.

“The child is both a hope and a promise for mankind.”

Montessori classrooms — filled with real materials, practical tasks, and opportunities for concentrated activity — mirrored the logic of nature itself: ordered freedom, purposeful exploration.

Nature, for Montessori, was not an “extra” but a fundamental teacher:

“When children come into contact with nature, they reveal their strength.”

She saw that when children are deprived of real work, real beauty, and real contact with the living world, they do not merely grow up ignorant — they grow up wounded.

In a Montessori environment, the child’s soul could breathe again.

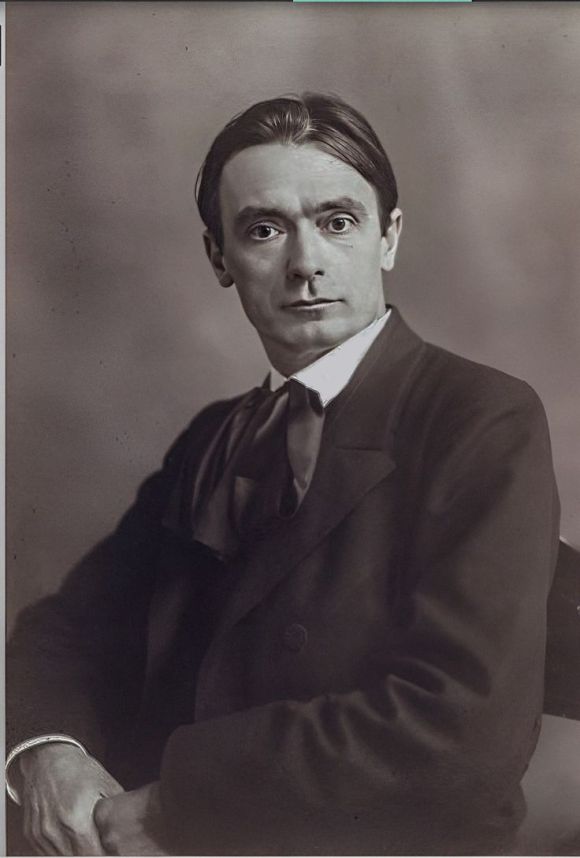

Steiner’s Prophecy: Rekindling the Spiritual Flame

Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Waldorf education, offered perhaps the most spiritually ambitious vision of education.

In The Education of the Child (1907) and later lectures, Steiner proposed that the human being unfolds through distinct phases, each requiring specific nourishment:

- The young child (0–7) learns through imitation and sense experience.

- The child (7–14) learns through imagination, story, and beauty.

- The adolescent (14–21) seeks truth through critical thinking and moral striving.

When education ignores these living rhythms, Steiner warned, it deforms the human being, creating adults disconnected from meaning, nature, and destiny.

“Receive the children in reverence, educate them in love, and send them forth in freedom.”

Waldorf education placed art, handwork, storytelling, and direct engagement with the seasons at the center of schooling — not as luxuries, but as essential pathways for the development of the whole human being.

For Steiner, education was a cosmic task: to midwife the emergence of free, creative souls capable of healing the world.

Conclusion: The Urgency of Rebellion

Across centuries and continents, these thinkers saw through the illusions long before the rest of us: Education, as it stands today, is not broken. It is functioning exactly as it was designed — to feed the engines of capitalism, to produce compliant workers, to sever us from the land, from each other, and from ourselves.

It is no accident that a system built to serve profit would also accelerate the polycrisis — the interwoven catastrophes of climate collapse, social fragmentation, and spiritual emptiness.

Rousseau, Illich, Holt, Freire, Montessori, Steiner — they gave us the seeds of another possibility. A world where learning is life itself. Where children are not molded, but unfold. Where education reconnects us to nature, community, and the deep wellsprings of meaning.

But these seeds must be sown deliberately, fiercely, and soon. The time for polite reforms is over. We must deschool the world, reclaim the Earth, and awaken the children — before there is no world left for them to inherit.

🌿 A Day in the Life of a Liberated Child: An Imaginary Portrait 🌿

The morning sun spills like honey over the forest clearing where the small learning community has gathered. No bells clang. No roll calls drone. Here, education begins with breath, with barefoot feet on dew-kissed earth, with the slow awakening of wonder.

The child — let’s call her Anaya — does not walk into a “classroom.” She walks into life itself, living and learning as one continuous, joyful motion.

Rousseau’s Voice: The Freedom to Grow Naturally

Anaya is not rushed, lectured, or drilled. Like Rousseau’s Emile, her education unfolds according to the rhythms of her own nature. “Plants are shaped by cultivation, and men by education… we are born weak, we need strength; we are born ignorant, we need understanding.”

Anaya climbs trees to study the structure of leaves, follows ants to understand cooperation, feels the tug of hunger before learning about farming. Knowledge is not poured into her — it blooms from within, in direct dialogue with the world. She is trusted to become, not molded to perform.

Illich’s Voice: Deschooling the Mind

There are no formal schools here. No authorities with chalk and ruler. As Illich envisioned, learning is embedded in community life itself. “School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.”

Anaya learns carpentry from an elder, herbal medicine from a healer, astronomy by sleeping under the stars. She accesses “learning webs” — mentorships, skill-sharing circles — not rigid curriculums. Her education is stitched into real life, not suspended from it.

Holt’s Voice: Trusting the Child’s Inner Compass

No one measures Anaya’s “progress” with tests or grades. As John Holt insisted, trust is sacred. “Children learn from anything and everything they see. They learn wherever they are, not just in special learning places.”

When Anaya spends three weeks building a tiny shelter with hand tools, no one interrupts to “correct” her. Adults observe quietly, ready to assist if invited. Her mistakes are seen as treasures — true learning in motion — not as failures to be punished.

Freire’s Voice: Dialogue, Not Domination

Learning happens through dialogue, not monologue. Following Paulo Freire, Anaya is treated as a co-creator of knowledge, not a passive receiver. “Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system… or it becomes the practice of freedom.”

During morning gatherings, children and mentors sit in circles, speaking of injustice, ecology, stories of peoples and struggles from across the Earth. They ask: What does it mean to live rightly? Anaya’s voice carries as much weight as anyone’s. Her questions shape the learning journey.

Montessori’s Voice: The Prepared Environment of Freedom

The spaces Anaya moves through are lovingly prepared — not to constrain her, but to invite her unfolding. As Maria Montessori knew, “The greatest sign of success for a teacher is to be able to say, ‘The children are now working as if I did not exist.’”

She chooses from a world of beautifully crafted tools, books, art supplies, gardens, and musical instruments. Materials are tactile, self-correcting, designed to spark her senses and her intellect without the need for constant adult intervention. Her environment whispers: You are capable.

Steiner’s Voice: Awakening the Whole Human Being

Anaya’s education nourishes not only her head, but her hands and heart. Inspired by Rudolf Steiner, her day weaves art, movement, storytelling, music, gardening, and handcrafts into intellectual pursuits. “Our highest endeavor must be to develop free human beings, who are able of themselves to impart purpose and direction to their lives.”

Each morning begins with singing and movement under the open sky. Lessons come alive through myth and poetry before diving into more abstract reasoning. Seasons, festivals, and natural rhythms form the true calendar of her learning. She knows herself not as a consumer of knowledge, but as a living, creative soul bound intimately to the Earth.

This is no utopia. It is simply education returned to its original task:

Not to forge citizens for a machine, but to midwife the unfolding of free, wise, connected human beings — children who can meet the polycrisis not with fear or obedience, but with vision, love, and fierce aliveness.