AI Podcast Summary of this Article

This podcast is a Google Notebook LM-based summary of my article. Those interested in a deeper dive can head to the article with greater details, pictographs and tables.

Introduction

The Upanishads, revered as the culminating wisdom of the Vedic tradition, represent a profound shift: from outward ritual to inward inquiry, from sacrificial fire to the inner light of self-knowledge. Composed between roughly 800 and 200 BCE, these Sanskrit texts mark a turning point in Indian thought, where metaphysical reflection began to take precedence over ceremonial performance. The earliest among them—such as the Bṛhadāraṇyaka and Chāndogya—emerged in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, giving voice to a deepening philosophical consciousness through dialogic teachings that invited personal introspection.

Scholars typically distinguish two major phases in the development of the Vedic Upaniṣads. The first, including texts like the Bṛhadāraṇyaka (BU), Chāndogya (CU), Taittirīya (TU), Aitareya (AU), and Kauṣītakī (KsU), is dated between 700 and 500 BCE and predates the rise of heterodox traditions such as Buddhism, Jainism, and the Ājīvikas. The second wave—encompassing the Kena (KeU), Kaṭha (KaU), Īśā (IU), Śvetāśvatara (SU), Praśna (PU), Muṇḍaka (MuU), Māṇḍūkya (MaU), and Maitrī (MtU)—spans roughly 300 to 100 BCE (Olivelle 1998: 12–13). In shifting focus from sacrificial rites to self-knowledge, the Upanishads marked a turning point in the Vedic tradition, birthing the philosophical currents that would come to define schools such as Vedānta, Sāṃkhya, and Yoga. Here, ritual gave way to reflection, and salvation was recast not as an external reward but as an inner liberation.

This intellectual metamorphosis culminating in the Upanishads unfolded within a broader global moment of spiritual awakening. Between 900 and 300 BCE, a strikingly parallel transformation stirred across Eurasia—from the forests of India to the cities of China, from the deserts of Persia to the shores of the Mediterranean. The German philosopher Karl Jaspers would later call this the Axial Age—a period in which human consciousness seemed to pivot, independently and simultaneously, in multiple cultures. In this epoch, new ethical visions arose, long-held norms were questioned, and the search for universal truths became a defining concern. Jaspers saw this age as the spiritual axis upon which the modern world still turns.

This report contends that the emergence of the Upanishads is not only central to the evolution of Indian thought but also a defining expression of the Axial Age itself. Across the ancient world, the Axial Age arose amid sweeping social, political, and economic transformations—urbanization, the rise of new political orders, expanding trade networks, and growing dissatisfaction with inherited religious forms. These shifts formed a crucible in which new modes of thought emerged, each culture responding in its own way. The Upanishads stand as the Indian articulation of this broader moment: a philosophical turning inward. The shift “from sacred fire to inner light,” the emphasis on the inner Agnihotram—the ‘ritual of introspection’—as a replacement for outward ritual, captures the essence of the Axial Age in India. It marks a profound reorientation, where liberation was no longer sought through prescribed rites but through inward, contemplative practice aimed at self-awareness and the realization of the self (Ātman) as one with ultimate reality (Brahman).

In Part 1 of this article, I will explore the Axial Age as a global phenomenon—the historical conditions that gave rise to it and the philosophical ruptures it produced across civilizations. In Part 2, I will turn to the Indian context, tracing how these transformations took shape on the subcontinent and culminated in the inward metaphysics of the Upanishads.

The Axial Age: A Global Awakening of Consciousness

The concept of the Axial Age, as theorized by Karl Jaspers, posits a period around 500 BCE, specifically within the broader spiritual process occurring between 800 and 200 BCE, as a pivotal turning point in human history. Jaspers observed a simultaneous and independent flourishing of universalizing thought across geographically diverse regions, including China, India, Persia, Judea, and Greece. This era witnessed the emergence of influential thinkers such as Confucius and Lao-Tse in China, the Buddha, Mahavira and the sages of the Upanishads in India, Zoroaster in Persia, the Hebrew prophets in Judea, and Greek philosophers like Parmenides, Heraclitus, and Plato. Jaspers characterized this period by a profound shift in human consciousness, where individuals became acutely aware of existence as a whole, of their own selves, and of their inherent limitations, prompting them to ask fundamental questions and strive for liberation and redemption. This era, according to Jaspers, laid the groundwork for the basic categories within which humanity has continued to think and the origins of the world religions that have shaped human civilization to this day.

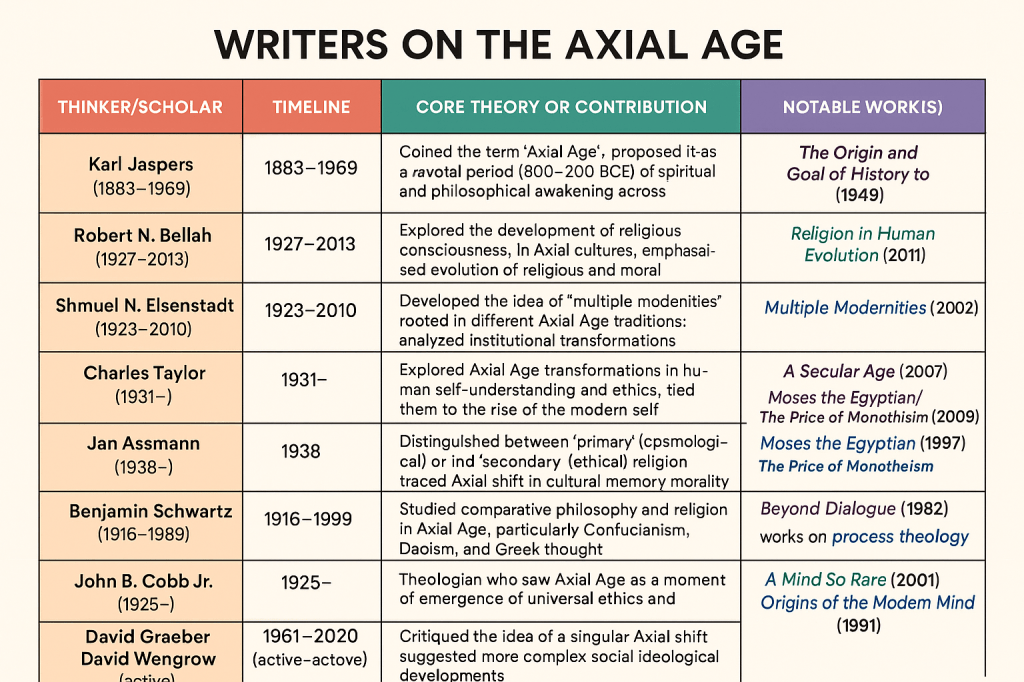

Several key characteristics define the Axial Age. One prominent feature is the emergence of universalizing thought, a move towards the articulation of universal truths, religious principles, and moral codes applicable to all individuals, transcending localized customs and beliefs. The Axial Age also marked an ethical turn in religious thought, with an increased emphasis on ethical behavior and the concept of a moralizing God or ultimate reality that demands righteousness and compassion. A critical aspect of this period was the critique of existing norms, where previously unquestioned ideas, customs, and social conditions were subjected to rigorous examination, questioning, and, in some cases, rejection. The Axial Age also saw a significant emphasis on the individual spiritual quest, with a shift towards individual values and a personal search for salvation or enlightenment, moving away from a primary focus on collective identity and ritualistic practices. Intellectually, the era was marked by a growing tension between rationality and myth, with a discernible struggle between logos (reason) and mythos (myth) as ways of understanding the world. Furthermore, the Axial Age witnessed the rise of traveling scholars who moved between cities, facilitating the exchange and dissemination of new ideas. These interconnected characteristics point to a fundamental shift in human thought, prioritizing universal principles, ethical conduct, individual introspection, and rational inquiry in the pursuit of truth and meaning. The following is a list of authors who have surmised the changes that happened across the globe during the Axial Age with varying emphasis on social, political, religious and economic factors.

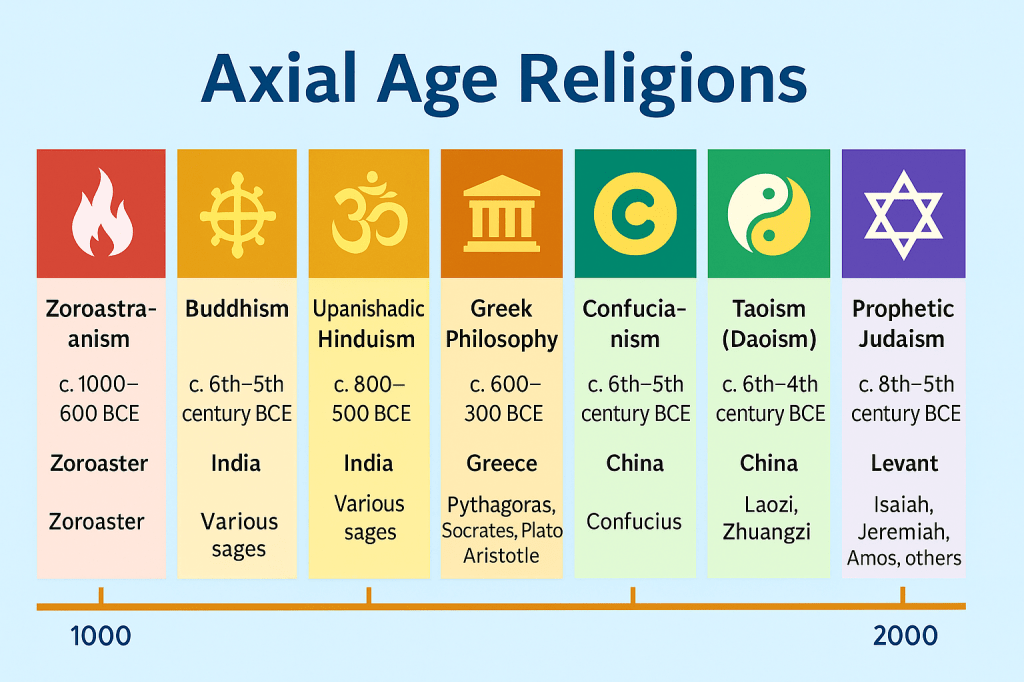

The Axial Age produced a diverse array of influential movements and thinkers across different cultures. In Persia, Zoroastrianism emerged, emphasizing the cosmic struggle between good and evil and the importance of individual moral choice. India witnessed the rise of early Buddhism, with its focus on the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and the principles of non-violence and asceticism. In Greece, the foundations of Western philosophy were laid by thinkers like Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, who championed reason and logic as tools for understanding the world. China saw the flourishing of Confucianism and Taoism, ethical and philosophical systems that emphasized social harmony, virtuous conduct, and living in accordance with the natural order of the Tao.12 In the Levant, Judaism underwent a significant transformation with the rise of prophets who emphasized monotheism, ethical monotheism, and social justice.13 These diverse yet contemporaneous movements illustrate a global pattern of intellectual and spiritual innovation, with different cultures offering unique responses to the evolving social and intellectual landscape of the time.

| Tradition/Philosophy | Region | Founder/Key Figures | Approximate Dates (BCE) | Core Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zoroastrianism | Persia (Iran) | Zoroaster (Zarathustra) | c. 1000–600 BCE (debated) | Moral dualism, free will, judgment after death |

| Buddhism | India | Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) | c. 6th–5th century BCE | Four Noble Truths, Eightfold Path, non-violence |

| Upanishadic Hinduism | India | Various sages (rishis) | c. 800–500 BCE | Self (Atman), ultimate reality (Brahman), moksha |

| Greek Philosophy | Greece | Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras | c. 600–300 BCE | Rational inquiry, ethics, metaphysics, political theory |

| Confucianism | China | Confucius (Kongzi) | c. 6th–5th century BCE | Filial piety, social harmony, moral cultivation |

| Taoism (Daoism) | China | Laozi, Zhuangzi | c. 6th–4th century BCE | Natural order (Tao), spontaneity, simplicity |

| Prophetic Judaism | Levant (Israel) | Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, others | c. 8th–5th century BCE | Monotheism, social justice, covenant with God |

History Behind The Rise Of The Axial Age

Human history saw the emergence of distinct cultural traditions, which can be broadly reduced to a few basic types of social organisation that appeared in historical succession.

In the infancy of our species, humans lived in kinship bands, which were relatively small and stable groups of closely related hunter-gatherers. In higher primates and early humans, social organisation was largely founded on genetic mechanisms. The principal mechanisms for solidarity and cooperation in kinship bands were genetic, specifically the dynamics of kin selection and reciprocal altruism.

Kin Selection: This is described as a genetic predisposition to cooperate freely with relatives, with cooperation being more spontaneous and extensive the closer the relation4. The logic is that “blood is thicker than water”. This mechanism became fixed genetically because it encouraged behaviours that assisted the survival of relatives carrying the same helping genes.

Reciprocal Altruism: This is presented as a genetically endowed predisposition for cooperating with nonkin. This occurs under circumstances where there is a high probability that favours given will be returned, following the logic of “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine”. Traits for initiating conditional alliances and retaliating against cheaters could become genetically fixed if the species could keep a tally of exchanges and if these traits offered significant survival value.

Kin selection and reciprocal altruism, operating together, constitute the genetic foundations for the kind of social organisation typical of higher primates and early humans.

While sufficient for kinship bands, relying solely on genetic means of solidarity had disadvantages. If kinship bands experienced an increase in size or increased density of population, this placed heavier demands on available resources. If conditions did not improve, the group would show signs of stress along family lines, leading to increased conflict and hostility until part of the group would organise and emigrate. This pattern of growth and fission (spreading out in response to environmental and social stress) was the norm for most of human history before the agricultural revolution. With settled agricultural societies, cultural means were needed to supplement the genetic factor to prevent social fission and expand solidarity and cooperation beyond the limits achievable by the genes alone.

This need for cultural means to supplement the genetic factor, prevent social fission, and expand solidarity and cooperation beyond the limits achievable by genes alone, in settled agricultural societies, ties directly into arguments made by some anthropologists about human cognitive capacities. They suggest that humans, while always possessing the capacity for symbolic thought and symbolically organized behaviour, only developed and fully put these abilities to use under the pressure of certain circumstances. For example, increasing population growth and consequent pressure on resources made it increasingly advantageous to be able to distinguish instantly between insiders and outsiders, and between persons of different status. One might argue that humans have always possessed the capacity for complex rational and imaginative thought. To overcome the limitations inherent in relying solely on kinship (as described previously) and to form larger, settled groups like tribal alliances, humans invented artificial bonding mechanisms from these very rational and imaginative thought abilities, specifically designed to supplement the genetic factor. In this they were simply making fuller use of features of the human mind that have existed always and everywhere. The ability of humans to develop articulate, cultural means of social organisation interacts extensively with genetic determinants of behaviour. Humans are genetically predisposed to associate and cooperate, but these dynamics are regulated by emotions that can be manipulated by symbols. This allows for the redirection of emotional responses and behaviours by modifying key symbols.

Through their thought faculties, humans developed artificial bonding mechanisms with the use of symbols, rituals, and conceptual tools that acted as external emotional triggers, allowing individuals to be manipulated into cooperating more easily, even when genetic signals were lacking. This symbolic framework redefined social boundaries, enabling people identified through shared symbols to be treated as kin, creating virtual kinship that mimicked real familial bonds. Symbolic markers such as body ornaments (tattooing, scarring), greetings, gestures, and clothing styles played crucial roles. Communal events strengthened inter-family bonds, while storytellers served as key cultural agents—retelling shared histories (even invented ones), articulating a common ancestry, and envisioning collective futures to reinforce group identity. Ceremonial gift exchanges further supported emotional ties like affection and gratitude and helped resolve conflicts.

Ultimately, this capacity to develop and elaborate cultural tools for social organization—interacting with but going beyond genetic determinants—is what most distinctly characterizes humans. This is basically a Story tradition, which, in the profound sense, integrate ideas about reality and value, forming a narrative core that organises culture and provides resources for solidarity and cooperation. Stories stabilise behaviour patterns by giving them legitimacy and normative status, showing how new ways of life fit into a larger scheme of meaning. These mechanisms enabled the transition from small kinship bands to stable, cooperative tribal alliances which supplemented hunting and gathering with light horticulture and herding. The transition from kinship bands to tribal alliances is considered perhaps the most decisive event in the history of the species, as it meant cultural factors would henceforth interact extensively with genetic determinants of behavior.

Further societal evolution saw the emergence of chiefdoms as a new form of social organisation, where some tribal groups wised up to new means of solidarity and cooperation. Chiefdoms replaced tribal consensus and decentralised decision-making with centralised authority in the figure of an absolute ruler. Solidarity was often affirmed through a contrived common descent from the chief’s clan, and the chief’s dominance was legitimised by myths of divine favour. Cooperation was assured through dependence, veneration, and fear, backed by military power. While more efficient and formidable, militarily, chiefdoms were notoriously unstable under stress, leading to uneven sacrifices, political unrest, culling (infanticide, wiping out villages), or wars of conquest (spread-out option). Their growth often strained administrative abilities, leading to inequity and political chaos. The “wisdom” was essentially the chief’s wisdom

The Axial Age came about with the inherent stresses and contradictions with the rise of chiefdoms or kingdoms. To solve the issues Axial Age thinkers used the same cultural techniques of “wising up” , i.e creating a new Story of Life, the way the old hunter gatherer tribes and the later chiefdoms had invented. In essence, the Axial Age stories provided a new foundation for solidarity and cooperation on a much larger scale than previously possible. By grounding morality in a universal, transcendent order and focusing on the transformation of the individual soul, they offered a way to create coherent social orders (like the state system, which emerged around this time) and achieve cooperation among diverse peoples, moving beyond the limitations and inherent instabilities of chiefdoms which relied heavily on the chief’s personal authority, fear, and limited, often contrived, group identities. While the Axial traditions didn’t fully achieve global unity, they significantly expanded human solidarity and cooperation to an unprecedented scale.

The table below gives a snapshot of the various the social, transitions that took place as humans moved from being hunter gatherers to tribal alliances to chiefdoms ruled by monarchs to modern states.

| Age / Period | Approximate Dates | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) | c. 2.5 million – 10,000 BCE | Hunter-gatherer societies; stone tools; control of fire; cave art; nomadic lifestyle |

| Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) | c. 10,000 – 8,000 BCE | Transitional phase; microlithic tools; early domestication; semi-permanent settlements |

| Neolithic (New Stone Age) | c. 8,000 – 3,000 BCE | Agriculture, animal domestication, pottery; permanent villages; megalithic structures |

| Chalcolithic (Copper Age) | c. 4,500 – 3,300 BCE | Use of copper tools; first metallurgy; early urbanization in some areas |

| Bronze Age | c. 3,300 – 1,200 BCE | Bronze tools and weapons; city-states; writing systems (e.g., cuneiform, hieroglyphs) |

| Iron Age | c. 1,200 – 500 BCE | Iron tools; larger empires; rise of historical religions; classical civilizations |

| Classical Antiquity | c. 500 BCE – 500 CE | Flourishing of Greece, Rome, India, China; philosophy, arts, and formal states |

| Middle Ages (Medieval Period) | c. 500 – 1500 CE | Feudal societies in Europe; Islamic Golden Age; rise of kingdoms and religions |

| Early Modern Period | c. 1500 – 1800 CE | Renaissance, Reformation, Age of Discovery, Scientific Revolution |

| Modern Age | c. 1800 – present | Industrialization, nation-states, modern science, digital revolution |

Social, Political and Religious Changes From Pre-Axial Societies to Axial Age

The period preceding the Axial Age, roughly around the sixth century B.C., was marked by significant challenges and turmoil in various parts of the ancient world. This was a time of increasing complexity and confusion.

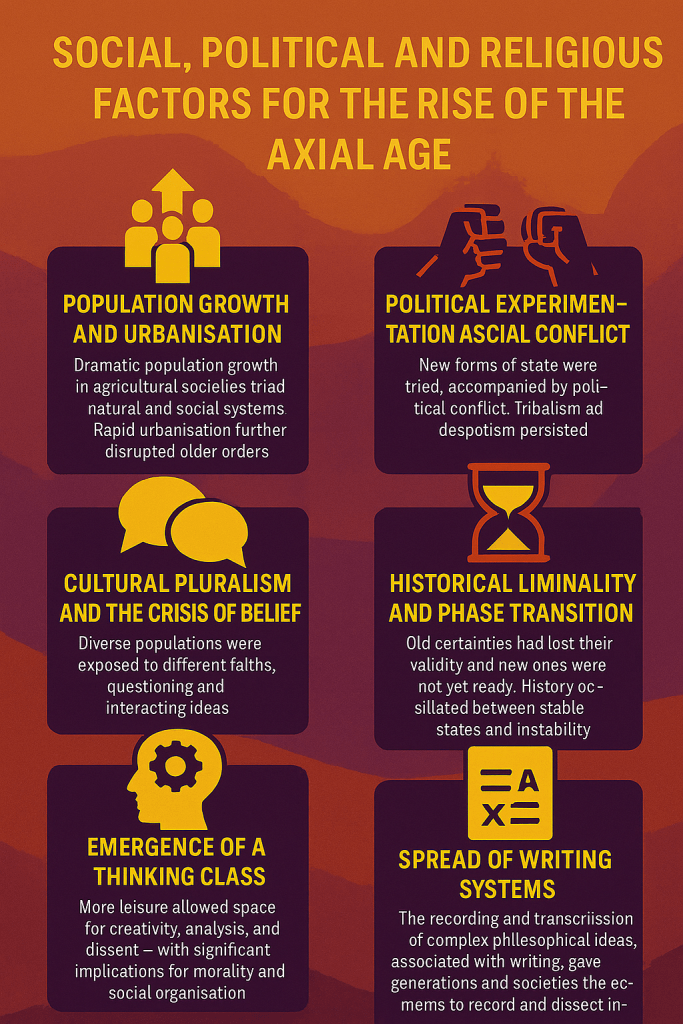

Population Growth and Urbanisation

As people moved from hunting and gathering to settled agricultural societies, populations were increasing dramatically in each of the axial regions, putting stress on natural and social systems. This stress led to increased options for warfare and mass migrations. A significant portion of the population increase was absorbed by cities, and rapid urbanisation created problems, particularly as new city dwellers came from diverse backgrounds. Increasing urban civilisation, initially under priestly leadership, encouraged trade and brought societies closer, but rapid urban expansion disrupted old orders.

Political Experimentation and Social Conflict

There was experimentation with the state system, which complicated social circumstances with false starts amid spasms of residual tribalism and despotism. This new way of living generated unprecedented social and political conflict, violence, and aggression.

Formation of Rigid Class Hierarchies and Social Stratification

As early civilizations scaled in complexity, class hierarchies hardened. Agricultural surplus, land ownership, and control of trade routes led to the consolidation of power among elites—rulers, priests, and landowners—while large segments of the population were relegated to laboring or servile roles. This increasingly rigid stratification was often legitimised through cosmology, religious doctrine, or myth, making social inequality seem divinely ordained or natural.

The psychological and ethical tensions created by these hierarchies became a central concern for Axial thinkers.

Cultural Pluralism and the Crisis of Belief

As diverse populations were drawn into close proximity through urbanisation, trade, and migration, people encountered a wide range of beliefs and practices different from their own. This exposure led to deep questioning of inherited traditions, rituals, and worldviews. The older religious and cultural systems, once taken for granted, began to lose their authority in the face of competing perspectives. The result was a crisis of legitimacy, as societies struggled to reconcile new diversity with established norms, creating the conditions for the emergence of new philosophical and ethical frameworks.

Historical Liminality and Phase Transition

In general, the pre-Axial Age can be described as an “interregnum” or historically liminal period between two ages of great empire, where “old certainties had lost their validity and new ones were still not ready”. The Axial Age can therefore be understood within a pattern where human history oscillates between relatively long “stable states” and shorter “phase transitions”. During these transitions, older dominant social structures prove inadequate due to growing populations, new technologies, and intensifying social conflicts.

Emergence of a Thinking Class

As agrarian societies grew more productive, and wealth and surplus became more available, certain social classes gained leisure—a condition essential for intellectual reflection and philosophical development. This emergence of a thinking class, including sages, priests, scribes, and ascetics, enabled a deeper inquiry into the nature of existence, morality, and social order. Freed from immediate survival needs, these individuals turned their attention to meaning, ethics, and metaphysics.

Spread of Writing Systems

Simultaneously, the spread of writing systems allowed for the recording and transmission of increasingly complex ideas. Where oral cultures relied on memory and repetition, writing enabled analysis, abstraction, critique, and accumulation of knowledge across generations. This fostered philosophical traditions that could grow over time and engage in self-correction and cross-regional exchange.

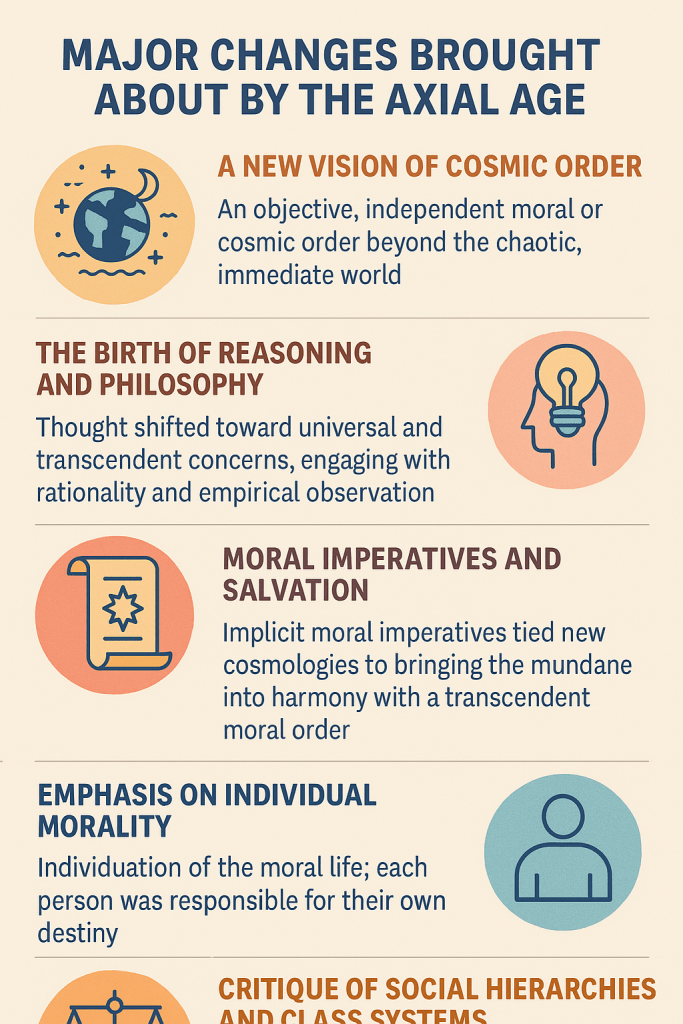

Major Changes Brought About by the Axial Age:

The Axial Age saw an explosion of new forms of wisdom, introducing significant transformations in the social and psychological organisation of the human species…. The prophets and teachers of this era told a new kind of story about how things are and which things matter to bring about order in the chaos caused in pre-Axial societies.

A New Vision of Cosmic Order

During the period known as the Axial Age (roughly 8th to 3rd centuries BCE), thinkers and spiritual leaders across various cultures observed the societal turmoil and perceived a fundamental disconnect between prevailing circumstances and a higher, ideal state of existence. This era saw the emergence of new philosophical and religious frameworks that interpreted this discord not merely as misfortune but as a consequence of failing to align human conduct with a deeper, often moral, reality. These traditions frequently posited the existence of an objective, independent moral or cosmic order that transcended the immediate, chaotic world.

A significant shift occurred in the perception of the divine and the mundane. Unlike many earlier traditions where the supernatural was deeply embedded in and often mirrored the earthly realm, Axial thought tended to accentuate the distinction between the this-worldly and an ‘otherworldly’ or transcendental domain. This often led to the development of dualistic perspectives, contrasting concepts such as the divine and the human, good and evil, and the sacred and the secular. A consistent emphasis was placed on the tension between the perceived imperfections of the mundane order and the reality of a higher, independent moral or spiritual order.

This period fostered a new level of human self-awareness. Individuals became more conscious of their place within the cosmos, their inherent limitations, and the often-terrifying aspects of existence. This led to profound questioning about the nature of reality, suffering, and the human condition, and a striving for liberation, salvation, or enlightenment. By confronting their limitations, individuals were seen as capable of aspiring to higher ethical and spiritual goals. Experiences of the absolute were sought both internally, in the depths of selfhood, and externally, through the concept of transcendence. Consciousness itself became an object of reflection and critical inquiry.

The Birth of Reasoning and Philosophy

The Axial Age marked a turning point, a conceptual “axis” around which thought shifted from predominantly local and immanent concerns toward universal and transcendent ones. While mythical narratives remained influential, particularly among the general populace, this era witnessed a growing engagement with rationality and empirical observation in examining the world and prevailing beliefs – a nascent “battle of logos versus mythos.”

The distinction between philosophy and religion was not familiar to ancient thinkers. One may distinguish, first, between those movements in India, Iran, and Israel that claimed divine revelation, and those in Greece and China that did not. The movements based on revelation were distinctive in the absolute certainty and social exclusiveness that their method demanded. Revelatory theology was a communal as well as an epistemological phenomenon. It created strong communities based on intellectual assent to certain propositions and/or behavior patterns. The difference was not that religious beliefs in China and Greece were less strongly held, but they did not claim these beliefs had been revealed in texts. Noticeably in both Greece and China, the supreme deity (Zeus/Heaven) was invoked by those supporting a radical re-evaluation of existing social and political structures, such as Solon, Mozi, and Aeschylus

Some thinkers in Greece and China may be called secular, Confucius and Protagoras for example. In Athens in particular, a questioning attitude toward religion and gods developed. Few Greek thinkers explicitly denied the existence of deities, but the powers ascribed to them were viewed with skepticism. Confucius urged his followers to focus on the problems of people here and now rather than the spirit world (Analects 6.12); he was not concerned with the afterlife, but much concerned with respect for the dead as well as a wide range of ritual conduct. Plato, on the other hand, while dismissive of current forms of religion, argued that dialectical philosophy made it possible to arrive at certain knowledge of divine being, but this could only finally be achieved when the divine revealed itself to the individual soul. Revelation was a matter of personal attainment, but it culminated in a mystical experience; one could not gain true knowledge of the divine by dialectic alone.

The philosophical enterprise was, above all, an invitation for people to think for themselves. Philosophy put the onus on the individual to respond; we find this in Confucius and the Buddha (and quite possibly, later, in Jesus); if I give them one comer and they don’t come back with three corners, then I don’t go on: Analects 7:8. A major innovation in Confucius and Socrates was asking questions without giving answers. This strategy could seem a kind of mind-play with little or no immediate social utility, but we can see that it had considerable social utility in the long term: it generated modern philosophy, without which scientific enquiry could not have proceeded beyond a certain point. Philosophy now became a distinctive human enterprise. Moral and scientific enquiry went together because both were looking for general principles; nature works according to regular laws. Open debate and enquiry were surely as important as any other new development.

Scholarly theories propose various drivers for these transformations. Some suggest a change in cognitive style, possibly facilitated by the spread of literacy and external memory tools like writing, which encouraged more analytical and reflective thinking compared to earlier narrative and analogical approaches. Others emphasize a shift in reward orientation, positing a move away from a primary focus on immediate, material rewards towards a greater value placed on long-term spiritual goals, which in turn fostered the development of self-discipline and altruism. While the precise causes and the extent of these changes are subjects of ongoing historical and sociological debate, the Axial Age undeniably represented a pivotal era in the development of human consciousness, ethics, and religious thought, the impact of which continues to resonate globally.

Moral Imperatives and Salvation

Religion became increasingly intertwined with ethical frameworks, elevating the importance of moral conduct as central to spiritual life. Existing myths were sometimes reinterpreted or transformed, gaining new layers of ethical and philosophical meaning, functioning more like parables that illustrated deeper truths. Implicit in the new cosmologies were moral imperatives that became central to various schemes for salvation. The transcendent moral order was often seen as governed by an eternal principle (like law, reason, or divine will) articulated as moral wisdom. Salvation was to be achieved by bringing the mundane order into harmony with this transcendent moral order. Ideas about death were revised, linking the quality of life beyond directly to one’s moral character in this world, unlike in most pre-Axial traditions where beliefs about immortality were not tied to moral behaviour.

Emphasis on Individual Morality

Perhaps the most significant achievement was a thorough individuation of the moral life. In contrast to pre-Axial societies where moral judgment was primarily a social phenomenon or the province of elites, Axial societies radically personalised obligations, rewards, and punishments. What we do tend to find now is a greater sense of individual as opposed to group moral responsibility, and a demand or appeal that individuals give their personal and voluntary consent to religious truths, or make their own judgment concerning what is true. All this implied individual self-determination in the most important affairs of life

This shift was accompanied by an “anthropological dualism” that detached the self (conceived as a soul or mind) as an independent unit from social and biological aspects of being. This self was seen as an entity that could and should be cultivated, refined, or purified through various measures like discipline, reason, piety, study, and ritual. Individuals gained a sense that their inner state and actions had consequences beyond their immediate circumstances.

The Axial Age movements offered resources for enriching the inner life, allowing each individual access to ultimate wisdom. Salvation became radically personalised, a possibility for each individual, no longer a vague quality of the group or the exclusive destiny of elite rulers. The Axial Age marked the rise of the individual, and humans emerged as “individuals” in the proper sense. This generated a new self-awareness, including awareness of autonomy and individuality. The human person as subject emerged, with awareness of the self in the present and after death. People began to formulate a more enlightened morality where each person was responsible for their own destiny.

Emphasis on Universal Solidarity and Cooperation

The social implications were profound, too. A further innovation, in certain instances, was the idea that all humans are equally capable of thought and, therefore, had access to the new enlightenment. In Greece and China, people were beginning to discuss what was appropriate for human beings as such rather than for the members of one tribe, class, or nation. Philosophy focused upon human rather than tribal characteristics. The wisdom and principles of the new story traditions were pronounced with cosmic significance, intended for the entire species, transcending ethnic and national pluralism. This introduced a new ideal of universal solidarity and cooperation, replacing the provincialism of the past. The oneness of humanity, though never fully realised, was clearly conceived. The strategy for achieving this oneness involved the transformation of individual souls. New social institutions like schools, churches, and monasteries emerged with a universal mission to transform the social order by transforming individuals. By individualising moral sensibilities and universalising moral ideals, these traditions significantly expanded human solidarity and cooperation to an unprecedented scale. There was a universal transformation of mankind. The Axial period laid the basis for universal history and spiritually drew all men into itself. Experience, accessible to man as man, became the basis of solidarity. When the three worlds that experienced the Axial Age meet, a profound understanding is possible, as they recognise their concerns are the same and deeply affect each other. Those peoples who did not participate in the Axial Age developments remained “primitive” and largely outside the stream of history until drawn in through contact or they died out. Axial Age societies had a greater capacity for social organisation, harmony, and long-term stability. Accountability to a higher authority, such as God or divine law, emerged, replacing the King God with a secular ruler accountable to a higher order….

Although the Axial traditions did not succeed in giving birth to a global culture, they are credited with the most impressive “wising-up” operation in human history, expanding solidarity and cooperation on a scale previously unimaginable. The Axial Age brought an end to many old civilisations, with ancient cultures persisting only in elements assimilated into the new beginning. The monumental aspects of earlier religions and state formations were seen in a new light and their meaning changed. Mankind today still lives by what happened, was thought, and created during the Axial Age, often returning to this period for new inspiration. The concept of the Axial Age is considered a foundation for a universal view of history, providing something common to all mankind beyond differences of faith.

Critique of Social Hierarchies and Class Systems

In all the breakthroughs of the Axial Age, there was a new application of thought to the problems of society. Thinkers across various civilizations sought alternatives—revolutionary or conservative—to the political mindsets of their time. Central to this shift was the concern with modifying instinctive behavior, especially in matters of violence and sexuality, and presenting these modifications as necessary in light of the way things actually are. Both Homer and the Mahabharata highlighted the consequences of unbridled instinct in advanced societies. These cultural breakthroughs introduced principles of loyalty and good behavior that transcended the boundaries of family, clan, or tribe. By articulating ties and obligations beyond the traditional familial or tribal structures, these new ideas proved more effective for organizing large, complex societies. A notable yet often underemphasized feature of this age was the emerging critique of entrenched class and caste hierarchies. While earlier social orders were typically justified through divine sanction or cosmic necessity, many Axial Age thinkers began questioning the moral legitimacy of rigid stratification. From the Hebrew prophets’ calls for justice to the Buddhist rejection of caste and the Confucian emphasis on virtue over birthright, these critiques introduced ethical standards by which hierarchies could be judged and, in time, reformed.

While sacred monarchy had already enabled the transition from tribalism to statehood, what distinguished the Axial Age was the ontological foundation of its new ethics. In Indian thought, the cosmos itself was seen as upholding the four varnas, divinely ordained by the supreme deity. The Hebrew prophets invoked the authority of Jahweh, grounding their appeals for justice in sacred law. In China and Greece, the picture was more complex. The Confucians envisioned a universal empire required by Heaven, analogous to Indian and Israelite beliefs, but others turned to realpolitik or even to political inaction (wu-wei), which paradoxically could coexist. Greek innovation lay in the idea that the polis was a human construct, required not by divine will but by the necessities of human nature—moral and material alike. Greece uniquely fostered a wide range of views about governance, including democracy, and was the only civilization where multiple forms of government were theorized and debated.

The appeal of Axial Age thought to reason and individual conscience marked a shift toward a new kind of social contract—one based on the internal consent of individuals. These new frameworks increased self-discipline and societal resilience, since loyalty was directed not solely toward rulers or dynasties but toward political orders and underlying principles. The individual emerged as a primary moral agent, capable of transcending their social condition through spiritual and ethical growth. This transformation in moral imagination did not dismantle existing class systems overnight, but it laid the groundwork for future movements toward social justice, equality, and human dignity. What followed in history was indeed varied, but the foundational shift toward inner moral autonomy and the rational legitimacy of power was a defining legacy of the Axial Age.

Debates and Criticisms Surrounding the Axial Age Concept

It is worth noting that the historical validity and interpretation of the Axial Age are still debated among scholars. While the idea that profound changes occurred is widely accepted, there is disagreement on the underlying reasons and the precise geographical and temporal boundaries. Some criticisms point to a lack of a demonstrable common denominator across regions, a lack of radical discontinuity with other periods, and the exclusion of key figures like Jesus and Muhammad. Some recent research suggests that the concept of a specific “Axial Age” limited to certain Eurasian hotspots is undercut by historical evidence, but the notion of “axiality” as a cluster of traits emerging when societies reach a certain scale and complexity is more widely accepted. The Axial Age debate itself is seen by some as a religious attempt to provide political guidance for the future, drawing an analogy between the chaotic events leading to the Axial Age breakthroughs and the perilous political circumstances of the modern age.

Conclusion

Thus there is a deep, long arc of human transformation: from small, kin-based foraging bands to large, stratified, reflective civilizations of the Axial Age

The end of hunter-gatherer life set humanity on a long path of social complexity and spiritual dislocation. The Axial Age was a civilizational awakening, attempting to reconcile the depth and unity of forager wisdom with the new realities of vast, hierarchical societies.

This table below shows the deep continuity from the intuitive spiritual life of foragers to the reflective breakthroughs of the Axial Age, shaped by layers of increasing complexity, control, and ultimately, existential questioning.

| Period | Timeframe | Key Features | Spiritual Outlook | Social Structure | Historical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunter-Gatherer Societies | Pre-10,000 BCE | Nomadic, egalitarian, small kin groups; subsistence lifestyle | Animism; nature-based spirituality; no centralized religion or hierarchy | Egalitarian, fluid gender roles; shared resources | Deep connection to nature; minimal social stratification |

| Neolithic Revolution | ~10,000–3000 BCE | Agriculture, domestication, sedentary villages; food surplus | Fertility cults; Earth goddess worship; ancestor veneration | Beginning of private property, gender roles, labor division | Foundations of inequality, ownership, and religious hierarchy |

| Early Agrarian Civilizations | ~3000–1000 BCE | Cities, kingdoms, irrigation, writing systems | Polytheism; divine kingship; ritualized temple religions | Strong hierarchies (kings, priests, warriors, peasants, slaves) | Emergence of large states; growing alienation and social control |

| Pre-Axial Tension | ~1200–800 BCE | State expansion, warfare, trade networks; growing complexity | Mythological frameworks strained under new realities | Increasing discontent among commoners and thinkers | Ethical and existential questions begin to surface |

| Axial Age | ~800–200 BCE | Independent rise of philosophy, introspection, and ethical systems in China, India, Greece, Persia | Universal ethics, personal salvation, introspection, inner freedom; e.g., Upanishads, Buddhism, Confucianism, Greek philosophy | Shift toward individual moral responsibility; criticism of elite power | Birth of enduring spiritual and philosophical traditions; inner freedom as response to outer control |

In the Indian context, this awakening gave rise to the Upanishads—a profound body of philosophical literature that distilled the spiritual unrest and introspection of the Axial moment into one of the most enduring expressions of metaphysical insight. The Upanishadic vision, with its inward turn and radical rethinking of self, soul, and reality, stands as India’s unique contribution to the Axial transformation.

In Part 2 of this article, I will explore in depth how the Axial Age unfolded on the Indian subcontinent, tracing the cultural, social, and spiritual conditions that culminated in the rise of the Upanishadic corpus—a literature that redefined the path to liberation through inner realization rather than outward ritual.

2 replies on “The Upanishads and the Axial Age: From Sacred Fire to Inner Light – Part 1”

I enjoy most of your writings on Advaita, but this one feels too written by AI and does not resonate as well as your other writings. Also the ‘podcast’ video style is a very familiar AI cliché style that dumbs things down considerably. I am sorry my first comment is negative as I enjoy your thoughts on Shankaracharya and the history of Advaita quite a lot.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I am sorry that you feel this way. I have found the AI podcasts of exceptionally high quality. Some of my friends too have commented on its good quality. Nonetheless I have registered your feedback too. I urge you to read the rest of my articles, following this one, and see whether your thoughts persist.

LikeLike