AI Podcast Summary of this Article

This podcast is a Google Notebook LM-based summary of my article. Those interested in a deeper dive can head to the article with greater details, pictographs and tables.

Introduction

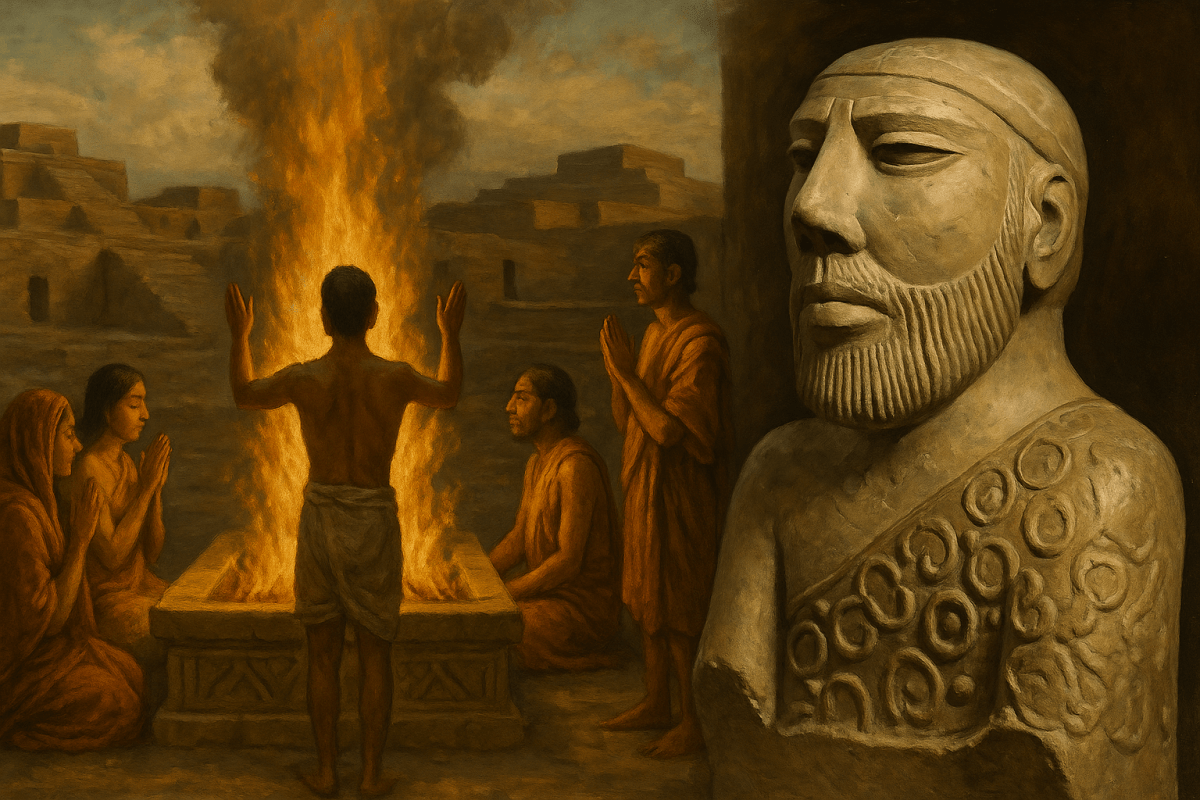

In Part 1 of The Upanishads and the Axial Age: From Sacred Fire to Inner Light, I traced the quiet birth of the Upanishadic vision against the backdrop of one of humanity’s great turning points—what Karl Jaspers called the Axial Age. This was no isolated awakening. Across the ancient world—from the Greek polis to the Chinese warring states, from Hebrew prophets to Indian sages—something stirred. Political structures fractured, societies reoriented, and a new kind of inner life began to take shape.

I explored how these shifts—driven by social and political upheavals, ecological strain, and spiritual exhaustion—unleashed a global wave of introspection. The sacred fire that once burned on ritual altars began to move inward, lighting up the question of self, meaning, and the ultimate. The Upanishads, then, were not a solitary Indian revelation, but part of a larger human moment: a collective reckoning with the old gods, the old orders, and the old ways of being.

In Part 2, the focus turns to the Indian subcontinent itself—not yet Vedic, but already in motion. I will trace the social, political, and religious changes unfolding in pre-historic and proto-historic India, which together form the cultural soil from which later Vedic and eventually Upanishadic thought would emerge. Pre-historic India refers to the period before the advent of writing, when knowledge of human life comes from archaeology—tools, dwellings, and burial sites. Proto-historic India marks the threshold where writing existed, but has not yet been fully deciphered, such as with the Indus Valley Civilization. These early epochs are often seen as mute, but they speak volumes when read through the patterns of settlement, trade, ritual, and emerging hierarchies.

By understanding these roots, we begin to see how India’s Axial turn did not arise in a vacuum—it was seeded in centuries of slow shifts, long silences, and quiet revolutions.

Re-Cap of Social Organizations Preceding the Axial Age

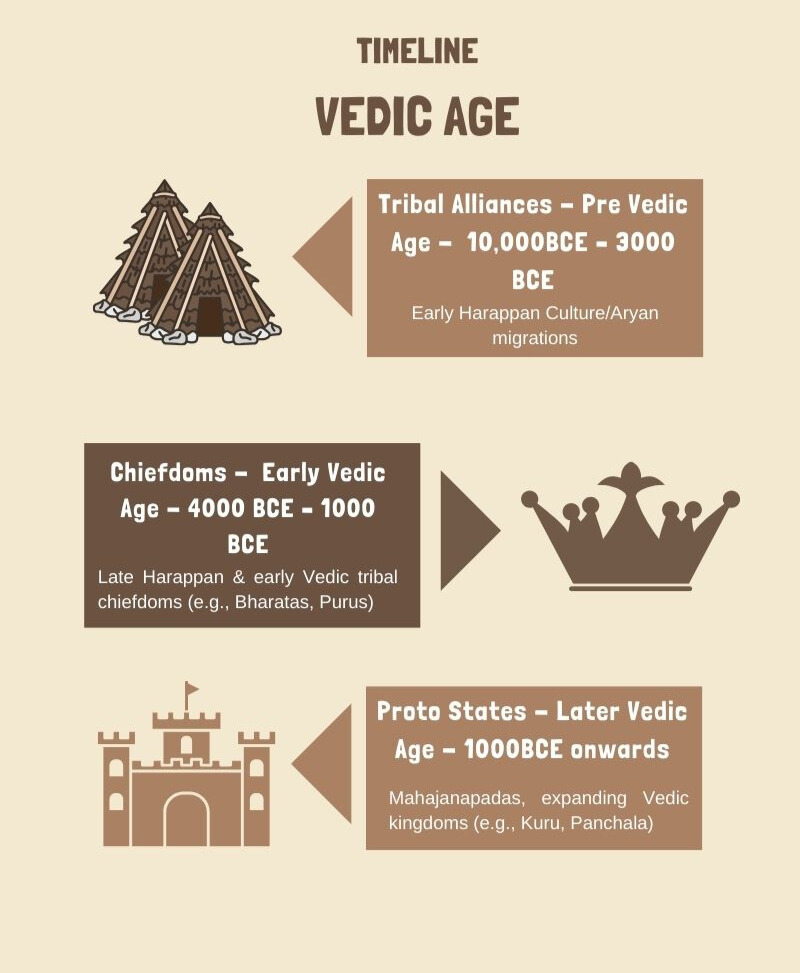

Before we turn fully to the Indian landscape, it’s worth pausing to recall the social worlds humanity inhabited before the Axial Age dawned. These forms of organization—tribes, chiefdoms, early kingdoms—shaped the rhythms of life for millennia. Revisiting them now offers more than just context; it invites a clearer understanding of the rupture the Axial Age represented.

The table below offers that recap—an outline of the social foundations that set the stage for transformation.

| Stage | Approximate Timeframe | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinship Bands (Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Age) | 2.5 million years ago – ~10,000 BCE | Small, nomadic groups (20–50 people) – Organized by kinship – Egalitarian – Foragers/hunters | Early Homo species (habilis, erectus), Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens |

| Tribal Alliances (Neolithic and Chalcolithic/Copper Age) | ~10,000 BCE – ~3,000 BCE | Larger, settled communities – Agriculture and domestication – Kin-based tribes – Part-time leadership | Natufian culture, Neolithic villages in the Indus, Nile, and Fertile Crescent |

| Chiefdoms (Chalcolithic and Bronze Age) | ~4,000 BCE – ~1,000 BCE | Centralized leadership under a chief – Social hierarchy – Redistribution of resources – Emerging religion & ritual power | Pre-dynastic Egypt, Early Harappan cultures, Minoan Crete, Mississippian cultures |

| Proto-States (Iron Age) | ~1,000 BCE – ~600 BCE | Larger territories under kings – Permanent administrative roles – Codified rituals and laws – Fortifications, taxation | Vedic Mahajanapadas (Kuru, Panchala), Neo-Assyrian Empire, Zhou Dynasty (China) |

Next, laying side by side the global movements with the specific movements in India, we can better trace how global currents echoed through the Indian subcontinent, and how the upheavals here were part of a larger human story in motion.

Social, Political and Religious Developments in the Indian Sub-Continent

1. Stone Age Kinship Bands

Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Cultures

The Indian subcontinent was inhabited by hunter-gatherer communities throughout the vast span of the Stone Age, encompassing the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods. These early populations adapted to diverse environmental niches across the region, from the rock shelters of Bhimbetka in central India to the caves of the Kurnool region in the south and sites in the northwest like Sanghao. Their survival was based on exploiting the available flora and fauna, utilizing a range of stone tools that evolved over time, including handaxes, cleavers, flakes, and later, smaller, more refined microliths during the Mesolithic. Evidence suggests these were typically small, mobile bands of people, likely organized into egalitarian societies, constantly moving in search of food resources. Archaeological findings, including tools and remains found at their dwelling sites, provide insights into their subsistence strategies and way of life before the advent of settled agriculture.

Palaeolithic Spiritual Practices

While direct evidence of complex religious systems is scarce for the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, the emergence of symbolic thought in the Upper Palaeolithic is suggested by cave paintings and personal adornments. These might indicate early forms of animism, shamanism, or beliefs related to the natural world and animals. Animism is a belief that animals, trees, rivers, and other natural elements had spirits or consciousness. Shamanism is not a single, unified religion but a set of beliefs and practices found in many indigenous cultures around the world. Shamanism centres on the idea that certain individuals, called shamans, can interact with the spirit world to heal, gain wisdom, or guide others.

Shamanism is a spiritual and healing tradition that is believed to be one of the oldest forms of religious practice in human history.

Mesolithic Spiritual Practices

Evidence from the Mesolithic period, particularly from sites like Bhimbetka rock shelters, includes a wealth of cave paintings depicting not only hunting and daily life but also scenes that are interpreted as dances, rituals, and communal gatherings. Burial practices, where the dead were sometimes interred with tools or food, suggest a belief in some form of afterlife or a continuation of existence after death. The discovery of objects like decorated ostrich eggshell beads might also hold symbolic or ritualistic significance. The move from Palaeolithic to Mesolithic saw Indian religion evolve from personal, animistic, and shamanic practices toward community-based symbolic rituals — setting the stage for more complex religious systems like those of the Neolithic, Harappan, and later Vedic periods.

While these findings clearly demonstrate that Mesolithic people had spiritual beliefs and practices, the archaeological record lacks the sculpted human or animal figurines that are typically associated with the concept of idol worship as it appears in later periods like the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age.

Therefore, while Mesolithic people had a spiritual life expressed through rituals, burials, and art, the evidence available does not support the idea that they engaged in the worship of idols in the form of sculpted images.

The transition from the Stone Age (Mesolithic) to the Neolithic period in the Indian subcontinent was a major shift from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled agriculture and animal domestication. This change was primarily driven by a warming climate after the last Ice Age, which altered the environment and resource availability. The climate became warmer and wetter, leading to the expansion of forests and a change in the availability of wild plants and animals. This altered landscape presented new opportunities and challenges for human populations. It is important to note that early farmers did not turn to farming out of choice but were pushed out of fertile regions by their hunter-gatherer compatriots. Pushed into semi-arid regions, they had no choice but to grow their own food. Thus almost all the early Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in South Asia are in semi-arid zones.

This transformative process occurred at different times across the subcontinent, laying the groundwork for future complex societies.

Neolithic Cultures

The Neolithic period, varying in its timeline across different regions (roughly from 7000 BCE onwards in some areas), saw the domestication of plants and animals, the development of pottery, and the establishment of villages. Important Neolithic sites are found in diverse areas, including Mehrgarh in the northwest (now Pakistan), sites in the Belan Valley, and those in South India, each exhibiting regional variations in practices and material culture. Before the discovery of Mehrgarh, most scholars believed that the Harappans had their antecedents either in the Mesopotamian or the Elamite civilisations to the West. The discovery of Mehrgarh put an end to this speculation and took a settled, agrarian way of life in the Indian subcontinent back to almost 8,500 years ago. It was at Mehrgarh that archaeologists found the earliest known remnants of the first farmers in South Asia. Excavations at Mehrgarh have revealed evidence of early farming of barley and wheat, as well as the domestication of cattle, sheep, and goats. The presence of mud-brick houses, granaries, and artefacts related to farming underscores its importance as an early agricultural settlement. Neolithic cultures continued to sprout all over the Indian subcontinent over the next few millennia, from Kashmir to Karnataka and Assam to Orissa. These soon led to the evolution and transition to the Chalcolithic cultures of the Deccan, Central India, the Vindhyas, the Canga Valley, Bengal and Orissa, but none of these cultures evolved into an urban civilisation like the one that emerged from the dusty site of Mehrgarh. (https://www.peepultree.world/livehistoryindia/story/lost-cities/mehrgarh-the-dawn-of-a-civilisation-8000-bce-2500-bce)

Neolithic Spiritual Practices

With the advent of settled agricultural life in the Neolithic, there is some evidence suggesting a growing focus on fertility and possibly early forms of deity worship. Figurines, sometimes interpreted as representations of a Mother Goddess associated with fertility and abundance, have been found at some sites (though these interpretations can be debated). Burial practices continued and in some cases became more elaborate, further indicating beliefs about the afterlife or the importance of the deceased. Structures or arrangements of stones might hint at ritualistic spaces. The pics below show the ruins along with Mother Goddess sculptures of Mehrgarh.

The Baghor stone, an Upper Palaeolithic object found on a platform with yellow pigment, has been interpreted by some as an early shrine possibly related to mother goddess worship, with ethnographic parallels drawn to modern tribal practices. At the heart of the Baghor shrine lies a unique triangular stone, revered as a manifestation of the Mother Goddess. The object was found placed on a circular platform, indicating intentionality in its positioning—a possible ritualistic act by the site’s inhabitants. This stone symbolises fertility, protection, and the nurturing aspects of nature, aligning with similar depictions of Mother Goddess worship across ancient cultures worldwide. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer’s analysis confirmed that the stone dates back to approximately 9000 BCE, making it one of the earliest known cult objects in the Indian subcontinent. The continuity of worship, from its Upper Palaeolithic origins to the present-day rituals performed by local tribal communities, underscores its timeless spiritual resonance. The shrine serves as a living museum, where the past and present coexist. It reminds us of the universality of certain symbols—like the Mother Goddess—which transcend time and geography to embody humanity’s shared reverence for life, fertility, and the mysteries of existence.

In summary, the Neolithic period sees the emergence of settled agricultural communities and the production of pottery and rudimentary figurines (human and animal). While these figurines suggest an interest in representing forms, their exact function is often debated. They could have served various purposes, including toys, decorative items, or having symbolic significance related to fertility or other aspects of life. Interpreting these early figurines definitively as “idols” that were worshipped in a structured way is not universally accepted by archaeologists. While the presence of figurines is a step towards material representations, it doesn’t conclusively prove widespread or defined idol worship akin to later periods.

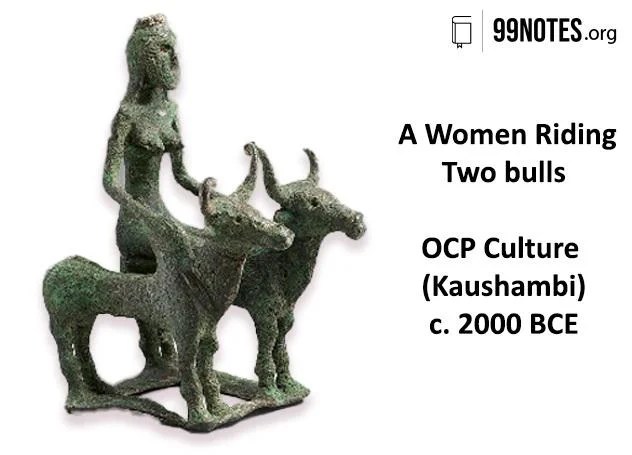

2. Chalcolithic/Copper Age Tribal Alliances

The Early Chalcolithic period, often overlapping with later Neolithic phases, is characterised by the introduction and increasing use of copper alongside stone tools. This era saw the rise of distinct regional Chalcolithic cultures across the subcontinent, such as the Ahar-Banas culture in Rajasthan, the Malwa culture in Central India, and the Jorwe culture in Maharashtra. While building upon the settled agricultural life of the Neolithic, the ability to work with copper allowed for the creation of new types of tools and objects, improving efficiency in some tasks and enabling the development of new crafts. This technological advancement, coupled with the continuation of settled life and evolving societal needs, marked this crucial period, paving the way for the subsequent Bronze Age.

Chalcolithic Spiritual Practices

The transition from Neolithic to Chalcolithic saw a move from more generalised and less archaeologically explicit spiritual expressions to more formalised practices centered around specific deities or symbols, with clearer evidence of rituals like fire worship and more diverse burial traditions. The increased sedentism and developing social structures of the Chalcolithic likely contributed to the emergence of these more defined spiritual practices.

- Emergence of specific cults: There is clearer and more abundant evidence for the worship of specific entities, most notably the Mother Goddess (through numerous terracotta figurines) and Bull worship (indicated by figurines and other depictions). These likely reflect the increasing importance of fertility in their agrarian society and the significance of cattle.

- Clearer evidence of fire rituals: The discovery of fire altars at many Chalcolithic sites strongly suggests the widespread practice of fire worship and associated ceremonies, which were not as clearly evidenced in the Neolithic. The Chalcolithic is marked by copper smelting, which required controlled fire. This associated fire with transmutation, power, and possibly the divine spark of creation. Smiths often had semi-magical or priest-like status—fire was seen as both technical and sacred.

- More elaborate and varied burial customs: While belief in the afterlife continued, Chalcolithic burials often show greater variation in type (e.g., urn burials, specific body orientations, fractional burials) and the quantity/variety of grave goods, potentially indicating more developed rituals or social distinctions related to death and the deceased.

- Increased use of terracotta figurines: Beyond the Mother Goddess, a wider range of terracotta human and animal figurines are found, providing more material for interpreting their religious beliefs and potential pantheon. While in the Neolithic, symbolic representation and possibly very early forms of venerating images might have existed, the archaeological record provides much stronger and more widespread evidence for the use of figurines as objects of apparent religious veneration in the Chalcolithic period. Therefore, while the conceptual roots of using images in spiritual practice might be older, the Chalcolithic marks the period where this practice, akin to early “idol worship” involving recognizable figures (especially of the Mother Goddess and the Bull), became a more discernible and significant aspect of the religious landscape in India. The shift from foraging to agriculture (especially grain cultivation) placed new importance on the fertility of land, crops, and people. The Mother Goddess became the symbolic source of life, echoing the earth’s fertility.

The bull was central to plough-based agriculture—pulling ploughs, tilling land. As the male complement to the fertile earth, the bull symbolised vital force, productivity, and strength. Later, this evolved into the Nandi bull associated with Shiva.

3. Bronze Age Culture – Indus Valley Civilisation

The transition from the Copper Age (Chalcolithic) to the Bronze Age in the Indian subcontinent marked a significant technological leap, fundamentally changing the types of tools, weapons, and objects that could be created. While the Chalcolithic saw the initial use of copper alongside stone, the Bronze Age is defined by the widespread adoption and mastery of bronze metallurgy.

The primary reason for this transition was the discovery and utilisation of bronze, an alloy typically made by combining copper with tin. Bronze is significantly harder and more durable than pure copper. This made bronze tools and weapons more effective and longer-lasting for tasks such as farming, crafting, and warfare

The adoption of bronze metallurgy required not only the knowledge of alloying but also access to tin. Unlike copper, tin sources are relatively scarce in many regions of the Indian subcontinent. This necessitated the development of trade networks to acquire tin from areas where it was available, both within and outside the subcontinent. The need to secure tin resources likely played a role in the expansion of trade routes and interactions between different regions and cultures, and contributed to the growth and complexity of societies, as exemplified by the urbanised Indus Valley Civilisation.

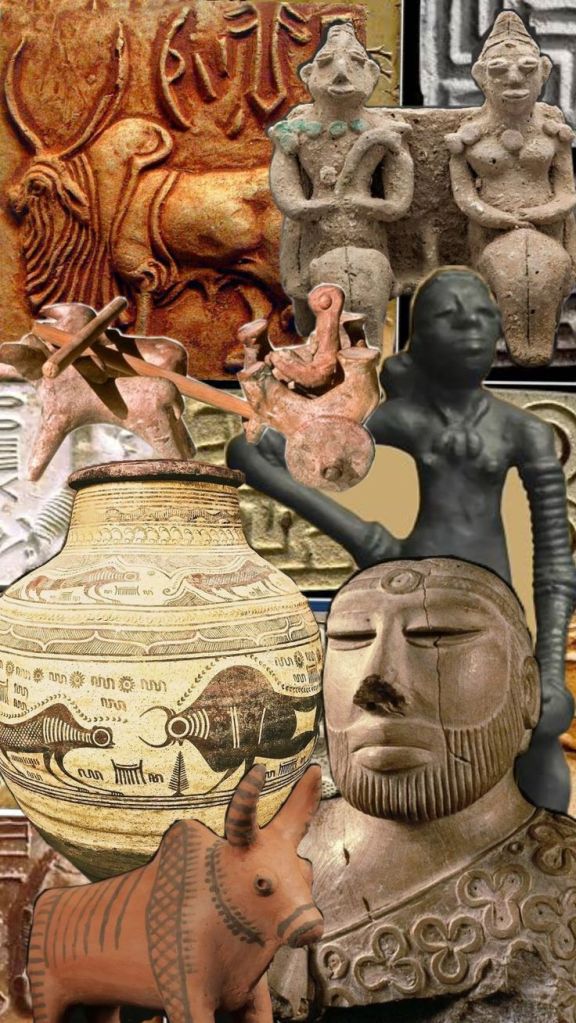

The Indus Valley Civilisation (circa 3300-1300 BCE) is the most prominent Bronze Age culture of the Indian subcontinent, showcasing a highly developed bronze metallurgy. The Harappans produced a wide array of bronze artefacts, including tools, weapons, vessels, and sculptures like the famous “Dancing Girl,” demonstrating their skill in alloying and casting. The sophistication of their bronze work highlights the successful transition from the earlier, more limited use of copper.

Bronze Age Spiritual Practices

The Indian Bronze Age is largely represented by the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC). The Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilisation demonstrates a development in spiritual practices towards more complex, possibly more standardised, and archaeologically visible forms of worship compared to the preceding Chalcolithic cultures.

While there are overlaps, particularly in the worship of fertility symbols and bulls, the key differences between the spiritual practices of the Chalcolithic Age vs the Bronze Age lie in the scale, complexity, and the emergence of more defined iconography in the Bronze Age IVC. They are:

- Increased Scale and Urban Context: Chalcolithic spiritual practices are inferred from village-based, often regional cultures. The IVC’s practices are associated with a large, urban civilisation, suggesting a more organised or standardised set of beliefs across a wider area, although regional variations likely still existed.

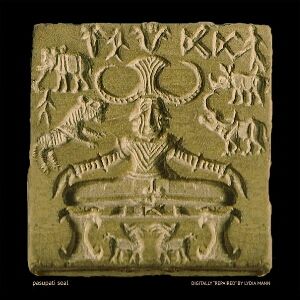

- More Defined Deity Iconography: While the Chalcolithic had terracotta figurines suggesting a Mother Goddess and possibly male figures or animal cults, the IVC provides more elaborate seals with complex depictions, such as the “Pashupati” seal, offering clearer (though still debated) iconography for specific deities or divine figures. The Pashupati seal depicts a seated male figure with a horned headdress, often in a yogic posture, surrounded by animals. This figure is frequently interpreted as a prototype of the later Hindu god Shiva, sometimes referred to as “Pashupati” (Lord of Animals). This suggests reverence for a powerful male deity connected to animals and possibly asceticism or yoga.

- Evidence of Public Ritual Structures: The IVC features larger structures like the Great Bath and more clearly identifiable fire altars at specific sites, indicating public or communal ritual spaces that go beyond the smaller, more localised ritual indicators of the Chalcolithic villages.

- Sophistication of Symbolic Representation: The seals of the IVC exhibit a higher degree of artistic and symbolic sophistication compared to Chalcolithic terracotta art. The complex compositions on some seals suggest developed mythological or religious narratives.

- Possible Emergence of Proto-Yoga: The seated posture of the figure on the “Pashupati” seal, which depicts a horned figure seated in what resembles Mulabandhasana or a proto-yogic posture, has led to interpretations related to early forms of yoga or meditation, a concept not clearly evidenced in the preceding Chalcolithic period.

The development of the yogi figure in the Indus Valley Civilisation likely emerged from:- The pressures and consciousness shifts of early urban life

- Shamanic or animistic traditions before that revered altered states and animal-human symbolism

- Early ritual practices centred on water, purity, and meditation

- A cultural continuity that carried symbolic and spiritual frameworks forward into the Vedic age. While we can’t point to a “yoga manual” in Harappa, the seeds of yogic consciousness—meditative postures, inner focus, connection with nature, and spiritual discipline—were already being sown.

- Emphasis on Water Rituals: While water bodies were important in the Chalcolithic (living near rivers), the Great Bath provides strong evidence for a specific, large-scale ritualistic use of water in the IVC, setting it apart from documented Chalcolithic practices.

In summary, based on archaeological evidence, the key difference in spiritual practices between the Copper Age (Chalcolithic) and the Bronze Age (represented primarily by the Indus Valley Civilization – IVC) in India lies in the scale, complexity, and organization of religious expression, largely influenced by the urban nature of the Bronze Age civilization. Here’s a breakdown:- Scale and Organisation: Chalcolithic spiritual practices are inferred from scattered village cultures across various regions, showing local variations in figurines, burial customs, and the presence of fire altars. The Bronze Age IVC, on the other hand, was a vast, urban civilisation. Its spiritual practices, while likely having regional nuances, show signs of greater standardisation and organisation across a wide area, befitting a complex urban society.

- Complexity of Iconography and Symbolism: While the Chalcolithic period has tangible representations like Mother Goddess and bull figurines, the IVC provides more complex and detailed iconography on seals, such as the figure interpreted as “Proto-Shiva” in a yogic posture surrounded by animals, and more varied symbolic motifs. This suggests a potentially more developed mythology or theological framework.

- Ritual Structures: The IVC features large-scale structures with apparent ritualistic purposes, most notably the Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro (suggesting ritual bathing) and organised fire altars at sites like Kalibangan and Lothal. While fire altars existed in the Chalcolithic, the monumental scale and integration of structures like the Great Bath into urban planning are characteristic of the Bronze Age IVC.

4. Iron Age – Vedic Civilization

Decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC)

For a long time, the dominant theory for the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation was deemed to be the invasion of Aryana who came from the West (various homelands proposed, including Central Asia, Europe). Modern archaeological evidence, however, strongly rejects the outdated Aryan invasion theory, pointing instead to a natural and multifaceted decline. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation—once a thriving network of sophisticated urban centres—was the result of a complex mix of environmental and economic factors. The drying of the Sarasvati River, triggered by tectonic shifts and a weakening monsoon, disrupted the lifeblood of the civilisation’s heartland around 2000 BCE. A prolonged drought, ecological strain from deforestation and over-farming, and a sharp collapse in trade further eroded its urban structure. Rather than a sudden fall, the civilisation gradually unravelled, transitioning into smaller rural communities.

Transition to the Iron Age

The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation led to a slow and complex transition into the Iron Age, shaped by a mix of environmental, cultural, and technological factors. As the Sarasvati River dried up due to tectonic shifts and declining monsoons, major urban centres like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa became unsustainable. Populations gradually dispersed into smaller rural settlements, giving rise to regional Late Harappan cultures such as the Cemetery H, Jhukar, and Painted Grey Ware cultures. These retained many Harappan traditions—like pottery styles and craft techniques—while adapting to new local conditions.

The collapse of long-distance trade with Mesopotamia and Central Asia forced a turn toward localised economies and subsistence farming. Ecological stress, including deforestation and overuse of land, further pushed this shift. Around 1800–1200 BCE, iron technology began to appear in areas like eastern Punjab and the Ganges Valley, enabling forest clearance, expanded agriculture, and stronger tools. This technological shift played a key role in supporting new agrarian communities.

Social organisation became more decentralised, and elements of Harappan religion and symbolism—such as the pipal tree and fire altars—continued into emerging Vedic and regional traditions. Over centuries, these changes laid the foundation for the fully developed Iron Age cultures that would define early historic India.

Continuity Between IVC and Later Cultures

There is significant evidence demonstrating continuity between the Harappan (Indus-Sarasvati) civilisation and later Indian culture. This includes:

- Continuity in town planning elements, brick usage, and drainage

- Persistence of religious and ritualistic practices, such as fire altars, worship of deities like Siva (Pasupati, Trisula, Linga-cum-yoni), Mother Goddess and Nature worship, and practices like Yoga and meditation.

- Continuation of social stratification patterns

- Everyday customs like the use of vermilion in the hair parting by married women and specific types of bangles

- Continuity in agricultural practices, such as the criss-cross furrowing pattern

- Use of weights and measures

- Certain games and folk tales

- While the horse and spoked wheel were once claimed to be absent in the Harappan civilisation by proponents of the Aryan Invasion Theory, the sources provide evidence of their presence in Harappan and earlier levels, further supporting continuity.

The Harappans as the Authors of the Vedic Age

Modern scholars argue against the traditional view that the Vedic period (associated with the Rigveda) came after the decline of the Harappan Civilisation due to an invasion or migration. Instead, they propose that the Rigvedic people were indigenous and were the authors of the Harappan Civilisation. The Rigveda frequently and extensively describes the Sarasvati River as mighty and glorious. Archaeological, hydrological, and dating evidence suggests the Sarasvati significantly weakened after 5000 BCE and dried up around 2000 BCE due to climate change and tectonic activity. This indicates the Rigveda must have been composed before the river dried up, placing it at least in the 3rd millennium BCE, and potentially earlier (4th-5th millennium BCE), aligning its date with the flourishing period of the Harappan Civilisation. Additionally, the territory described in the Rigveda (from the Ganga-Yamuna in the east to the Indus and its western tributaries in the west) is precisely the area occupied by the Harappan Civilization during the 3rd millennium BCE. This strong overlap in time and space supports the idea that they were the same people.

Along with this, the continuity in later cultures, as noted above, suggests that the Harappans are the Vedic people themselves, and the Vedas and the Harappan Civilisation are seen as two aspects – the literary and material expressions of the same civilisation.

Conclusion

As we draw this exploration of India’s deep past to a close, Part 2 has traced the intricate tapestry of social, political, and religious life that unfolded across millennia, long before the renowned Axial Age ‘inner turn’ took full flight. From the nomadic kinship bands of the Stone Age, whose spiritual lives are hinted at through animism and shamanic practices, we followed the slow, profound shifts brought by settled agriculture in the Neolithic, hinting at early fertility worship through debated figurine interpretations and significant early cult objects like the Baghor stone. The Chalcolithic period saw the emergence of more defined cults, particularly focused on the Mother Goddess and the Bull, alongside clearer evidence of fire rituals and varied burial customs, marking a more discernible practice of image veneration. This culminated in the sophisticated urban civilisation of the Indus Valley, the Bronze Age heartland, where religious expression appears on a grander scale, featuring complex iconography like the Pashupati seal, potential proto-yoga practices, and large public ritual structures such as the Great Bath.

This journey reveals that the remarkable introspection and reorientation characteristic of India’s Axial Age did not arise ex nihilo. Instead, they were seeded in centuries of slow shifts, long silences, and quiet revolutions, a continuous evolution of human society and its relationship with the sacred, stretching back to the earliest inhabitants. The evidence increasingly points to a profound continuity between the Harappan (Indus-Sarasvati) civilisation and later Indian culture, suggesting the Harappans themselves may have been the authors of the Rigvedic tradition, viewing the material and literary aspects as expressions of the same people inhabiting the same territory during the same flourishing period. The transition into the Iron Age further built upon these foundations amidst environmental and societal changes.

Thus, the rich and complex spiritual landscape of pre-Vedic and proto-historic India provided the essential cultural soil from which the later developments would sprout. The shifts from external nature reverence towards symbolic representation, structured rituals, and even early hints of inner practice like proto-yoga laid the foundational layers, demonstrating that the move towards a more internalised spiritual life was a long process.

In Part 3 of this series, we will immerse ourselves fully in the world of the Vedic culture. We will explore its structure, rituals, and the development of its philosophical thought, tracing how these ancient traditions, built upon the deep foundations explored here, finally culminated in the profound insights of the Upanishads – the very texts that so powerfully articulate the Axial Age shift from sacred fire to inner light that we began our journey by exploring.

The following table summarises the various social and political changes that happened in the Indian subcontinent across the pre-historical and proto-historical ages of India, culminating in the Iron Age.

| Global Social Stage | Timeframe (Global) | South Asian Context | Corresponding Vedic Phase | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunter-Gatherer Bands | 2.5 million years ago – ~10,000 BCE | Stone Age tribes in India (Bhimbetka, etc.) | Pre-Vedic (Before 1500 BCE) | Palaeolithic to Mesolithic (Stone Age) – Small nomadic groups (20–50 people) – Kin-based, egalitarian – No formal leadership – Foraging and hunting – No written or oral texts from this period |

| Tribal Alliances | ~10,000 BCE – ~3,000 BCE | Neolithic and early Chalcolithic cultures (Mehrgarh, early Harappan) | Pre-Vedic / Proto-Indo-Aryan migrations | Neolithic to Chalcolithic (Late Stone Age to Copper Age) – Settled agricultural communities – Lineage-based tribal groupings – Part-time leaders or elders – Pottery, domestication, early rituals – Oral traditions may have begun developing among Indo-Aryan migrants but no formal Vedic texts yet |

| Chiefdoms | ~4,000 BCE – ~1,000 BCE | Late Harappan & early Vedic tribal chiefdoms (e.g., Bharatas, Purus) | Early Vedic Age (c. 1500–1000 BCE) | Bronze Age to early Iron Age – Hereditary chiefs (rajas), supported by tribal councils (sabha, samiti) – Growing social hierarchy – Resource redistribution – Cattle as wealth – Composition of the Rigveda: hymns (samhitas) praising nature gods (Indra, Agni, Varuna) – Oral transmission through memorization |

| Proto-States / Early States | ~1,000 BCE onward | Mahajanapadas, expanding Vedic kingdoms (e.g., Kuru, Panchala) | Later Vedic Age (c. 1000–600 BCE) | Bronze Age to early Iron Age – Hereditary chiefs (rajas), supported by tribal councils (sabha, samiti) – Growing social hierarchy – Resource redistribution – Cattle as wealth – Composition of the Rigveda: hymns (samhitas) praising nature gods (Indra, Agni, Varuna) – Oral transmission through memorisation |

Here is a chart summarising the inferred spiritual/religious beliefs and practices of prehistoric and protohistoric cultures in India, based on archaeological evidence. It highlights the major differences and developments across the periods. It’s important to remember that for periods without written records (Palaeolithic through Chalcolithic, and the undeciphered script of the IVC), our understanding of their beliefs is based on the interpretation of material culture, which can be subject to different scholarly views.

Spiritual and Religious Aspects Across Ancient Indian Periods

| Aspect | Palaeolithic Age | Mesolithic Age | Neolithic Age | Copper Age | Bronze Age / IVC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Beliefs | Animism, totemism | Nature spirits, early community rituals | Proto-deity & fertility worship | Earth goddess, household deities | Anthropomorphic gods, divine kingship |

| Spiritual Focus | Spirits in animals, rocks, trees | Reverence for animals, hunting magic | Ancestors, rain, sun, fertility | Agriculture-linked divinities | Creator gods, protector deities, cosmic order |

| Rituals | Basic rituals, individual or clan-based | Shamanic, symbolic art in caves | Seasonal, agricultural, domestic | Public and domestic rituals | Shrines in homes, village centres |

| Burial Practices | Rudimentary; red ochre, body orientation | More grave goods, communal burials | Formal burials with pottery/tools | Distinct burial zones, terracotta figurines | Varied: elaborate graves (Kalibangan), urn burials |

| Symbols & Artifacts | Rock art, animal figures | Hunting scenes, fertility symbols | Female figurines, animal motifs | Terracotta mother goddesses, painted pottery | Seals with deities, unicorns, swastikas |

| Sacred Spaces | Natural sites (caves, rivers, hills) | Outdoor ritual spots, cave sanctuaries | Shrines in homes, village centers | Temples begin to emerge (e.g., circular platforms) | Planned temples, sacred tanks, fire altars |

| Divine Representation | Forces of nature, no human forms | Animal spirits, abstract forces | Figurines (female), sun, bull | Earth and fertility goddesses | Male-female deities, proto-Śiva (Pashupati) |

| Social Role of Religion | Clan-based, survival focused | Community bonding | Village cohesion, seasonal cycles | Emergence of priestly roles | Stratified society; religion tied to administration |