“He, O Gargi, who in this world, without knowing this Reality, offers oblations, performs sacrifices, practices austerities, even though for many thousands of years, gains little: his offerings and practices are perishable. He, O Gargi, who departs this life without knowing the Imperishable, is pitiable. But he, O Gargi, who departs this life knowing this, is wise.”

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad 3.8.10

Contents

Page 1

- Introduction

- Method of Self Inquiry in Advaita Vedanta

- Women in Vedanta

- Women in Vedic Period

- Subdued Status of Women in Upanishads

- Gargi Vachaknavi – Woman Philosopher Mentioned in the Brhadranyaka Upanishad

- The Story of Ubhaya Bharati: Woman Who Was the Judge in a Debate of Shankara vs Mandana

- Ideas and Questions that Arise from the Story of Ubhaya Bharati

Page 2

- Preface

- Tannupriya’s Journal: 13/8/2020

- Dialogue With Tannupriya on Awareness/Brahman

- Conclusion: Tannupriya’s Journal: 20/8/2020

Introduction

Yesterday, I had a dialogue on what is the ultimate reality according to Advaita Vedanta with one of the students in the Facebook NEEV Psycho-Philosophy Inquiry Study group that I run. She is an eighteen year old girl, who also happens to be a student of the NEEV School I ran between 2006-2017. I gave up running the school and all my organizational activities in 2017 to focus on teaching Self-Inquiry or Brahma-Vidya as it is called in Advaita Vedanta. When I started the NEEV Psycho-Philosophy Inquiry group, it was primarily because two of my students of the school, both of whom happen to be girls showed keen interest in continuing their self inquiry with me. In the past, I have already published two blog articles based on their journals and my dialogues with them in the study group. They are Attachment and Facing the Fear of Death and Choiceless Awareness of the Tree of Fear. The group was constituted on 18th May, 2020 and since then these two girls have been posting their self inquiry journals every day, to which I add my comments. As the inquiry deepens, it is natural for one to ask fundamental questions like what is death or what lies beyond death. In this article I am presenting a journal and dialogue with one of these girls – Tannupriya – on what is the Ultimate Reality of life.

While thinking about this article, it struck me that despite there being several boys in the group, it is only these two girls who have held on to self inquiry with such zeal; the boys (who are also students of NEEV School I ran) are content being passive observers to the group postings. This made me think about the role of women in the history of Vedanta. Though history does not account for much of a role for women in Vedanta, I thought it would be interesting to take a historical look of role of women in Vedanta along with my dialogue and journal of Tannupriya. In 3000 years of male dominated Vedanta history, these two girls, I hope, shall bring about a change.

Method of Self Inquiry in Advaita Vedanta

As I have previously discussed in detail in my article Shabda Pramana: Enlightenment through Words in Advaita Vedanta: Presenting a Dialogue, the method of inquiry in Advaita Vedanta is based solely on the three practices of Jnana Yoga called – Shravana (Listening/Reading Scriptures), Manana (Reflection/Dialogue) and Nidhidhyasana (Contemplation). In case a reader wants to know in greater detail about them, they can read here: Stages of Self Inquiry. How these are applied in the NEEV Psycho-Philosophy Study Group can be read here: NEEV Psycho-Philosophy Inquiry Study group

Shankaracharya, in his book explaining the method of teaching Advaita Vedanta – Upadeshasahasri, says the following:

We shall now’ explain a method of teaching the means” to liberation for the benefit of those aspirants after liberation who are desirous (of this teaching) and are possessed of faith (in it). (Verse 1)

He should first of all teach the Sruti texts establishing the oneness of the Self with Brahman such as, “My child, in the beginning it (the universe) was Existence only, one alone without a second,” “Where one sees nothing else,” “All’ this is but the Self”, “In the beginning all this was but the one Self” and “All this is verily Brahman”. (Verse 6)

After teaching these he should teach the definition of Brahman through such Sruti texts as “The Self devoid of sins”, “The Brahman’ that is immediate and direct,” “That which is beyond hunger and thirst”, “Not ‘-this, not-this”, “Neither gross nor subtle”, “This Self is not-this”, “It’ is the Seer Itself unseen”, “Knowledge -Bliss ”, “Existence ’-Knowledge Infinite”, “Imperceptible bodiless”, “That great unborn Self”, “Without the vital force and the mind,” “Unborn, comprising the interior and exterior ”, “Consisting of knowledge only”, “Without ‘ interior or exterior”, “‘ It is verily beyond what is known as also what is unknown” and “Called Akasha (the self-effulgent One)”, and also through such Smriti texts as the following : “It is’ neither born nor dies,” “It is not affected by anybody’s sins,” “Just’ as air is always in the ether,” “The individual Self should be regarded as the universe alone,” “It is called neither existent nor non-existent,” “As™ the Self is beginningless and devoid of qualities,” “The same in all beings” and “The Supreme “Being is different ; “—all these support the definition given by the Srutis and prove that the innermost Self is beyond transmigratory existence and that it is not different from. Brahman, the all-comprehensive principle. (Verses 7 & 8)

I thought it pertinent to share these verses not only to give a general idea to the reader about how the ultimate reality of Brahman is taught by the great Master himself – Shankaracharya – but also to show the same method is followed in a modern context and language by a teacher and student of this tradition more than a thousand years after the death of Shankara. This is the sampradaya, the spiritual family: an unbroken line of teachers and students that stretch from the creator Brahma to the present day. More on this can be found here: The Vedas Are of Non-Human Origin

Women in Vedanta

Women in Vedic Period

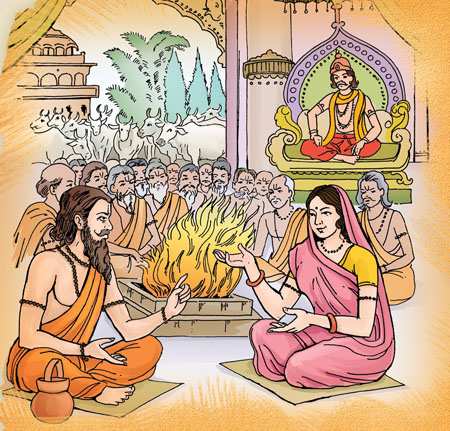

The Vedic period (2000-500 BCE) is seen specifically as a ‘Golden age’ for women. Women, in the Vedic era, so excelled in the sphere of education that even the deity of learning was conceived of as a female popularly known as ‘Saraswati’. Girls were allowed to enter into the Gurukulas along with boys. There are also instances of female Rishis, such as Ghosa, Kakhivati Surya Savitri, Indrani, Shradha Kamayani, Yami Shachi, Poulomi, Urvashi etc. Marriage in the Vedic Period was considered a social and religious duty and united the couple on an equal footing. The story of Gargi engaging in a philosophical debate with the King Yajnavalkya.

However, feminists are quick to point out that such a characterization is a superficial gloss. Out of over 1,000 hymns in the Rig Veda, only 12-15 are attributed to women. Clearly, this is not much cause for celebration. What this suggests is that women had limited access to sacred learning. An interested reader may refer to the link provided in the note from which I have drawn this information [1]

Subdued Status of Women in Upanishads

The Upanishads, (end portion of the Vedas), just as the Vedas and many other Hindu scriptures, were essentially composed with men in mind. The teachers were men, the students were men, and the authors were mostly men. Even the gods who are mentioned in them are mostly male gods. In this male dominated world of the Upanishads, sometimes you hear the faint voices of a scholarly woman, a dutiful wife or a responsible mother.

Apart from her, Maitreyi, Jabali, Usati Chakrayana’s wife, Janasruti’s daughter, Uma Haimavati, Satyakama Jabala’s wife are other women who appear in the Upanishads as the silent and subdued witnesses of a great era when spiritual wisdom unfolded through enlightened teachers of an ancient world. I am providing a link to an interesting article on the roles of women mentioned in the Upanishads here [2]

However, to be fair, we have to acknowledge that although women were not given much importance in the Upanishads, they were not degraded. We cannot also say that they had not been given any importance at all. For example, there is one chapter in the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad in which one long verse lists an entire lineage of about fifty teachers. What is special about it? All of them bear the names of their mothers as their last names to denote that men derive their greatness from their mothers since they influence their early development. This is the sampradya I mentioned earlier. Just to give an example I am quoting one of the three verses below

Verse 2.6.1 – Now the line of teachers: Pautimāṣya (received it) from Gaupavana. Gaupavana from another Pautimāṣya. This Pautimāṣya from another Gaupavana. This Gaupavana from Kauśika. Kauśika from Kanṇḍiriya. Kauṇḍinya from Śāṇḍilya. Śāṇḍilya from Kauśika and Gautama. Gautama—(Br. Upanishad)

There are also references to wives of spiritual teachers and women participating in debates and discussions. In one chapter of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Gargi appears in the court of King Janaka, and challenges Yajnavalkya, the best of the best, in a debate. From Yajnvalkya’s response, we learn that she was not an ordinary lady or a housewife. It’s interesting to hear the story of Gargi.

Gargi Vachaknavi – Woman Philosopher Mentioned in the Brhadranyaka Upanishad

Gargi is mentioned in the Sixth and the Eighth Brahmana of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, where the brahmayajna, a philosophic congress organized by King Janaka of Videha is described, she challenged the sage Yajnavalkya with perturbing questions on the Atman.This Upanishad is one of the primary or ‘mukhya’ Upanishad. It figures as number 10 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads. It is also one of the oldest, largest and important one.

Gargi Vachaknavi (born about 9th to 7th century BCE) was an ancient Indian philosopher. She was the daughter of sage Vachaknu in the lineage of sage Garga (c. 800-500 BCE) was named after her father as Gargi Vachaknavi. From a young age she evinced keen interest in Vedic scriptures and became very proficient in fields of philosophy. She became highly knowledgeable in the Vedas and Upanishads in the Vedic times and held intellectual debates with other philosophers. [3]

In Vedic literature, she is honored as a great natural philosopher, renowned expounder of the Vedas, and known as Brahmavadini, a person with knowledge of Brahma Vidya. Her philosophical views also find mention in the Chandogya Upanishad. Gargi, as Brahmavadini, composed several hymns in Rigveda (in X 39. V.28) that questioned the origin of all existence. The Yoga Yajnavalkya, a classical text on Yoga is a dialogue between Gargi and sage Yajnavalkya. Gargi was honoured as one of the Navaratnas (nine gems) in the court of King Janaka of Mithila.

In the Sixth and the eighth Brahmana of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, her name is prominent as she participates in the brahmayajna, a philosophic debate organized by King Janaka of Videha and she challenges the sage Yajnavalkya with perplexing questions on the issue of atman (soul). She is also said to have written many hymns in the Rigveda. She remained a celibate all her life and was held in veneration by the conventional Hindus. [3]

Here is an extract of the debate between Gargi and Yajnavalkya:

Dialogue Between Gargi and Yajnavalkya: Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 3.8

It was the court of King Janaka. Yajnavalkya received questions from all learned sages and seers assembled there, and he kept offering answers to all of them. Among them was a female sage Gargi, the daughter of Vachaknu. Addressing the assembly, she said, “Revered Brahmins, I shall ask Yajnavalkya two questions. If he is able to answer them, no one among you can ever defeat him. He will be the great expounder of the truth of Brahman.”

Yajnavalkya said, “Ask, O Gargi.”

Gargi said, “Yajnavalkya, that which they say is above heaven and below the earth, which is between heaven and earth as well, and which was, is, and shall be – tell me, in what is it woven, warp and woof?’

Yajnavalkya said, “That of which they say, O Gargi, that it is above heaven and below the earth, which is between heaven and earth as well, and which was, is, and shall be–that is woven, warp and woof, is the ether. “Ether (Akasha) is the subtlest element. So subtle that it is often indistinguishable from Consciousness. Without it nothing can exist. Yet there is more”.

Gargi said, “Thou hast answered my first question. I bow to thee, O Yajnavalkya. Be ready now to answer my second question.”

Yajnavalkya said, “Ask, O Gargi.”

Gargi said, “In whom is that ether woven, warp and woof?”

Yajnavalkya replied, “The seers, O Gargi, call him Akshara – the Immutable and Imperishable Reality. He is neither gross nor fine, neither short nor long, neither hot nor cold, neither light nor dark, neither of the nature of air, nor of the nature of ether. He is without relations. He is without taste or smell, without eyes, ears, speech, mind, vigor, breath, mouth. He is without measure; he is without inside or outside. He enjoys nothing; nothing enjoys him.’

“At the command of that Reality, O Gargi, the sun and moon hold their courses; heaven and earth keep their positions; moments, hours, days and nights, fortnights and months, seasons and years–all follow their paths; rivers issuing from the snowy mountains flow on, some eastward, some westward, others in other directions.’

“He, O Gargi, who in this world, without knowing this Reality, offers oblations, performs sacrifices, practices austerities, even though for many thousands of years, gains little: his offerings and practices are perishable. He, O Gargi, who departs this life without knowing the Imperishable, is pitiable. But he, O Gargi, who departs this life knowing this, is wise.”

“This Reality, O Gargi, is unseen but is the seer, is unheard but is the hearer, is unthinkable but is the thinker, is unknown but is the knower. There is no seer but he, there is no hearer but he, there is no thinker but he, there is no knower but he. In Akshara, verily, O Gargi, the ether is woven, warp and woof.”

Hearing these words from Yajnavalkya, Gargi again looked at the assembled Brahmins and said, “Revered Brahmins, well may you feel blest if you get off with bowing before him! No one will defeat Yajnavalkya, expounder of the truth of Brahman.”

The Story of Ubhaya Bharati: Woman Who Was the Judge in a Debate of Shankara vs Mandana

Shankaracharya too had a dramatic brush with a learned Vedantin woman by the name of Ubhaya Bharati. She lived approximately a thousand years after Gargi, somewhere around 700-750 A.D.

When Shankara was twelve years of age, he wrote his most profound commentaries on the Vedanta Sutras of Badarayana, the principal Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita which are known as Prasthanatraya, being the authorities on the Vedanta Sastras. The Bhashyas (commentaries) of Shankara are monumental works covering the import of the Vedic teachings and supplemented by clear reasoning and lucid exposition. This doctrine of Brahma Vidya which Shankara propounded through his works is what is known as Advaita Vedanta or Non-dualism or Purva Mimamsa. It confers salvation through the elimination of duality across the world.

Advaita Vedanta or Uttara Mimasa considered the Jnana Kanda – Knowledge portion, in which knowledge of Brahman is imparted, as the real purport of the teaching of the Vedas. However, there was another school, the older one, called Purva Mimamsa which considered the Karma-Kanda – ritualistc action portion of Vedas as the real purport of the Vedas and the performance of rituals as a way of salvation by gaining access to heaven.

Therefore, starting on his mission of popularizing his Purva Mimamsa or Advaita Vedanta, Shankara decided to go first to Prayag with a view to win over Kumarila Bhatta, the staunch upholder of the ritualistic interpretation of the Vedas and get his explanatory comments (Vartika) on his Bhashya on Brahma Sutras of Badarayana – Vyasa. Shankara realized that unless he was able to win over this powerful group of proponents and followers of ritualism, his goal to propagate his tenets as set out in his Prasthanathraya Bhashyas to the world would be incomplete.

Having reached Prayag, he came to know that Kumarila was about to enter into a fire, as an act of expiation for betraying his teacher from whom he had learnt stealthily the tenets of Buddhism. Sri Shankara rushed to the place where Kumarila had set himself to burn. Kumarila recognized Shankara, narrated to him his work against the Buddhists, his awareness about Sri Shankara’s Bhashyas and his desire to write a Vartika (explanatory treatise) on his Bhashyas. Kumarila explained how he was not in a position to break his vow of expiation and therefore asked him to meet his disciple Mandana Misra. He added that if Shankara could defeat Mandana Misra, whose actual name was Vishwaroopa, who was the most renowned protagonist of the Purvamimamsa School, it would clear all obstacles in the mission that Shankara had undertaken. Shankara then proceeded to Mandana’s place in the present-day Bihar.

There was a learned couple in the region we now know as Mithila in Bihar: Mandana Mishra and his wife Ubhaya Bharati. They were highly educated and followed the Vedic way of life. They were householders, who performed the rites and rituals designed to establish a household and make gods, sages and ancestors happy. They lived in harmony with nature and culture and followed the Mimansa school of thought, an enquiry of the soul. It was said that the best way to identify their house was to look for parrots, kept outside in cages, discussing issues on ontological and epistemological realities associated with the Vedas. As Mandana Misra was a distinguished practitioner of the Mimamsa philosophy, in his school of thought, a particular ritual is done, the results are achieved instantaneously. It displays a straightforward cause and effect relationship if practised accurately.

It was customary in the time of Shankara and Maṇḍana for learned people to debate the relative merits and demerits of the different systems of Hindu philosophy. So Shankara and Mandana agreed for a debate on the two schools they represented.

In the deliberations that followed, Bharati was made moderator. It is said that both men were exceptionally brilliant, but the garland around Mishra’s neck started to wither, for his body was starting to get agitated and angry. Though he was as intelligent as Shankaracharya, Mishra had not internalized wisdom. Therefore, he was not as calm as him. This led Bharati to declare Shankaracharya as the victor over her husband. Shankaracharya was impressed by her fairness. [4]

But she asked him how he could claim to have complete knowledge of the world, contained in the Vedas, if he was a bachelor and had never experienced sexual pleasure. Until he understood kamashastra, or the sensual arts, he could not consider himself to be fully immersed in Vedic wisdom. This created a dilemma. Shankaracharya had taken a vow of celibacy. How could he experience and gain knowledge of the kamashastra? Bharati smiled and said that was his problem. [4]

We are told that Shankaracharya then trained himself in the tantric secrets, enabling him to leave his body and enter the body of a dead king called Amaru in Kashmir. Through the reanimated body of Amaru, he experienced sexual pleasure. On returning to his original body, he met Bharati and explained how he understood kamashastra. Bharati then happily declared Shankaracharya the greatest Vedic scholar. [4]

Ideas and Questions that Arise from the Story of Ubhaya Bharati

This story is from Shankaracharya’s many biographies, composed 500 years after Shankaracharya died. It is quite possible that these are based on local folklore and may not have historical authenticity. However, this particular story draws attention to very interesting ideas. [4]

- That Sankaracharya was willing to have as judge in the debate his opponent’s wife was remarkable. It was the greatest testimony to his faith in the utter impartiality of Ubhaya Bharati. Sankaracharya knew that the discriminating power of the Buddhi (intelligence) was superior to the intellectual ability of the Medhas. One should understand the power of the Buddhi. It is not Buddhi as commonly understood—mere intellectual ability (Medha). It is intelligence in which Rita (Universal Order) and Sathya (Truth) are combined with Aasakthi (zeal) and Sthiratvam (steadfastness). Ubhaya Bharati was endowed with such intelligence. Buddhi is, thus, not only the capacity to think. Nor is it only the power of deliberation or the discriminating faculty. Beyond all these, it is the power of deep enquiry and judgement. Endowed with this capacity, Ubhaya Bharati decided in favour of Sankaracharya and against her husband. She declared that Sankaracharya had the better of the argument in the debate. This decision is based on Sathya and Ritam

- We have tensions between the householder arm of Vedic Hinduism and the hermit arm of Vedic Hinduism. There is also tension between the Vedic way of thinking, valuing the mind, and the tantric way of thinking, valuing the body and the occult arts. [4]

- In a modern take of the story, following his defeat, Mishra becomes an ascetic called Sureshwara and spreads Shankaracharya’s Advaita Vedanta around the world. He abandons the householder’s life and becomes a hermit. From this point, we stop hearing anything about Bharati. Why did Bharati, a scholar herself, give permission to her husband to turn into a hermit? Was becoming a hermit superior to being a husband? By making the hermit superior to the husband, the woman’s position is made inferior. In the monastic and occult traditions of India, the female position is always inferior and female biology is considered inferior to the male’s. We see this being reinforced by folklore that emerges from the monastic traditions of medieval India. [4][5]

Notes

- [1] – https://feminisminindia.com/2018/07/10/women-in-early-india-status/

- [2] – https://www.hinduwebsite.com/upanishads/wisdom/upanishads-day06.asp

- [3] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gargi_Vachaknavi

- [4] – https://devdutt.com/articles/who-is-a-hindu-the-importance-of-ubhaya-bharati/

- [5] – Modern scholars like M. Hiriyanna and Kuppuswami Shastri show that this story of Mandana becoming Shankara disciple Suresvara is not true

9 replies on “You Are Awareness/Brahman: Dialogue with a Teenage Girl & Women in Vedanta”

Wow! Clear, lucid exposition in this article about extraordinary personalities. But one comment: Advaita Vedanta isn’t Purva Mimamsa but Uttara Mimansa. You might’ve gotten the terms reversed in the article. And why are you using Wikipedia as a source (Western scholars are the major dominant force there, so people might find it harder to believe Shankaracharya was really 12 yrs old when he wrote the commentaries etc.) Is it just a part-post for members of the study group? Or scholarly information?

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment and words of appreciation. Thank you also for pointing out the Purva and Uttara Mimamsa error. I was totally oblivious of it. I shall edit it.

I am usually very meticulous about my information, spending hours and hours cross checking data from multiple authorities. I don’t consider Wikipedia to be the source of information. I consider the references cited in Wikipedia to be the source of information.

Well, that Shankara wrote his commentaries between the ages of 12 and 16 is what you shall find mentioned in all sources. It is not unlikely considering he died in the young age of 32 and taken sannyasa at the age of eight.

I don’t see any problems with Western scholars. Many of them have done extraordinary scholarly work in Advaita. Though again I read a wide variety of sources for information. For exegesis of his works I go by Swami Satchidanandendra Saraswati’s work mostly, followed by Swami Paramarthananda and Swami Dayananda Saraswati.

While I may speak very confidently about exegesis of Shankara’s work, I cannot claim that there cannot be variations in historical data I present. Indian history is notorious for lack of proper documentation and even scholars have a hard time reaching consensus on most data and dates. Thus I usually tend to give the sources which I have referred to in my article.

This article was meant for the wider audience, not just for the study group.

LikeLike

Thanks! I do love your deep inquiries on the blogs. I have to burning questions to ask for my spiritual path: Is brahmacharya (sexual abstinence) necessary for continuing effectively? Meditation has enhanced my mental focus and clarity, but as Swami Vivekananda said, a concentrated but impure mind is more dangerous than a scattered and pure mind. With the mental focus, while focusing on learning and meditation is good but I have problems stopping or dealing with strange sexual fantasies that start flowing into mind automatically, and am confused that (though I am able to suppress them a lot) suppression is not good and if I allow them to flow it just flows and … well that’s the problem. Should I allow it to happen and sexuality and everything to happen until it somehow runs out and lets me focus on the path?

Second question is more personal. I’ve heard that Jnanis come to path because they see the suffering of themselves as well as others and once they are enlightened do their best to enlighten others too while in their body. (Swami Vivekananda’s writings?) So you being self realized, you frequently state that you “dont want to be entangled in organizations” and just help people who themselves come to you and ask for help. So sometimes it can imply that you are somehow averse to worldliness (and aversion supposedly gets destroyed with knowledge?) and not selfless enough to let your body mind (your body mind would be the one averse yes? Because you are witness.) run its course and even so go ahead and propagate your teachings. You say you get angry and fight with wrongdoing. But if you declare yourself enlightened and gather a following like all the dhongi gurus but spread your real teachings, would it not be just as worthwhile (a necessary evil?) as you getting angry and knowing You are not angry…for the same reason you steer clear of organizations etc. Am I making sense?

Please clarify these.

LikeLike

Hello Brahmachari

I had told you to read all my articles because they would help you in getting a strong philosophical grounding for the questions you have raised and also help me in keeping the answers to your questions short. I am answering your questions now, assuming you have read the articles I had told you to read.

Brahmachari: Is brahmacharya (sexual abstinence) necessary for continuing effectively?

Anurag: Was Krishna a Brahmacharya? The path of liberation in Advaita is open both to householders and monks. The Upanishads has mentions of many householder jnanis like

1. Sage Yajnavalkya was a Jnani who is a preeminent Acharya

of Brahmavidya in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. His two

wives were: Kaatyaayini and Maitreyi.

2. King Janaka as a famed householder

3. Varuna was the Jnani-father of Bhrugu who was instructed

into Brahmavidya in the Taittiriya Upanishad

4. Sage Uddalaka was the Jnani-father of Shvetaketu in the

Chandogya Upanishad

5. Some Upanishads declare the fruit of Brahmavidya as

(also) – ‘In his, this Jnani’s, lineage, kula, there will be no

one who is not a Jnani’ [nAsya kule abrahmavit bhavati’]

This shows that the Jnani will be / can be a father.

Shankaracharya, being a monk and while strongly advocating monasticism treats these personalities of the Upanishads as ‘real’ and not imaginary. There is ample evidence for this treatment by him in his bhashyas.

Brahmachari: Meditation has enhanced my mental focus and clarity, but as Swami Vivekananda said, a concentrated but impure mind is more dangerous than a scattered and pure mind.

Anurag: Meditation is only a secondary means to self-realization and not the ultimate means in Advaita of Shankara. The ultimate means is Self Knowledge through Jnana Yoga. Meditation is a means in the Yoga School of Patanjali. The two paths are different. Swami Vivekananda mixed these two paths. I almost never do formal meditation. In Advaita we have something called Asparsha Yoga as described by Gaudapada.

Brahmachari: With the mental focus, while focusing on learning and meditation is good but I have problems stopping or dealing with strange sexual fantasies that start flowing into mind automatically, and am confused that (though I am able to suppress them a lot) suppression is not good and if I allow them to flow it just flows and … well that’s the problem. Should I allow it to happen and sexuality and everything to happen until it somehow runs out and lets me focus on the path?

Anurag: There is no “one size fits all” solution. Since I have clarified to you that even householders can become Jnanis, you can decide to marry. All depends upon your particular mental and emotional make-up. The Upanishads had the four stages of life scheme – Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha and Sannyasa – designed for intelligent exhaustion of vasanas. Like any schemes, however, one can take it elastically, not as a rigid rule to be followed. Some may follow it rigidly. It depends. Vasanas can be exhausted through Karma Yoga in a dharmic way by a householder. As Krishna said in BG 7.11:

“O best of the Bharatas, in strong persons, I am their strength devoid of desire and passion. I am sexual activity not conflicting with virtue or scriptural injunctions.”

In case you would like to take up Brahmacharya, it should be your svabhava, an inner nature. In this case, the struggle will not be “too much”. But if this is not your svabhava your vasanas will keep propelling you to fruition. In this case, it would be a wiser decision for you to marry. As Gita says in verse 3:35

“It is far better to perform one’s natural prescribed duty, though tinged with faults, than to perform another’s prescribed duty, though perfectly. In fact, it is preferable to die in the discharge of one’s duty, than to follow the path of another, which is fraught with danger.”

So you need to intelligently decide for yourself whether the path of Brahmacharya or the path of Grihastha is suitable for you. Both lead to Jnana. I chose the path of Grishastha. But I communicated to my partner that my path is that of Moksha. There was a mutual agreement on this.

Brahmachari: Second question is more personal. I’ve heard that Jnanis come to path because they see the suffering of themselves as well as others and once they are enlightened do their best to enlighten others too while in their body. (Swami Vivekananda’s writings?) So you being self realized, you frequently state that you “dont want to be entangled in organizations” and just help people who themselves come to you and ask for help.

Anurag: Yes, the above is true. I did social work for a decade and found that the root problem in the world is avidya. Till that is not resolved, the suffering of the world cannot be solved. I do not want to be entangled in organizations any longer because I want to help people with self inquiry rather than work for expanding my organization. I am not averse to it growing organically. As I write, gradually the number of people seeking my help and studying and assimilating Advaita through Jnana Yoga is slowly increasing. But my focus is not on numbers. My attempt is that I am genuinely able to help every individual. I have not stopped NEEV Centre for Self Inquiry. In fact it is slowly taking shape now organically.

Brahmachari: So sometimes it can imply that you are somehow averse to worldliness (and aversion supposedly gets destroyed with knowledge?) and not selfless enough to let your body mind (your body mind would be the one averse yes? Because you are witness.) run its course and even so go ahead and propagate your teachings.

Anurag: As you know that there are two realities here: Jnani as Self and Jnani as phenomenal self. The phenomenal Jnani keeps changing. For instance Ramana Maharshi got realization at an early age but for the next seventeen years or more he would be engaged in meditation/samadhi in Virupaksha Caves. After that one day he made himself available for people. A jnani goes through a long phase of stabilization and exhaustion of vasanas. Thus each Jnani lives differently from another Jnani on the basis of their vasanas. Some live active lives, some withdrawn, some teach, some don’t. And all these can also keep changing as one continues living. At present I feel the need to remain relatively silent and finish off with my residual afflictive vasanas, making myself available in a limited way. This may change in future depending upon the vasanas.

Brahmachari: You say you get angry and fight with wrongdoing. But if you declare yourself enlightened and gather a following like all the dhongi gurus but spread your real teachings, would it not be just as worthwhile (a necessary evil?) as you getting angry and knowing You are not angry…for the same reason you steer clear of organizations etc. Am I making sense?

Anurag: My anger has got nothing to do with organizations. All that is well past now. Neither do I need to protect myself from getting angry because I don’t get angry with external situations now. THe anger I talked about had to do with my wife majorly because of my vasanas and prarabdha karma internally and our specific relationship issues externally. The most intimate relationships bring out the deepest vasanas to the fore.

All this has got cleared now. Though all that I had to pass through was earth shattering in a phenomenal sense. It was only due to Self Knowledge that I could bear the impact. I wrote about how I enetertained thoughts of suicide in this phase in my article: “How Does A Jnani Person Deal With the Negative Impacts of the World: Part 1/2 – Titiksha” here https://neevselfinquiry.in/2020/11/16/how-does-a-jnani-person-deal-with-the-negative-impacts-of-the-world-part-1-2-titiksha/

Hope my answers have settled all your doubts. In case you have further doubts please let me know.

Warm wishes,

Anurag

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment and your questions. I shall definitely answer your questions in detail. Meanwhile I would like you to read my three part article series on “Prarabdha Karma After Self Realization” starting from here: https://neevselfinquiry.in/2020/09/24/prarabdha-karma-after-self-realization-its-philosophy-part-1-3/

Do write back to me after you read them and reframe or ask your questions again if they still remain.

In case you would like to join our Advaita Study Group to discuss these questions, please let me know.

Lastly Swami Vivekananda did not teach Shankara Advaita. He actually taught a version, which I call Yoga-Advaita. In Shankara Advaita samadhi is not the means to enlightenment.

LikeLike

Thank you very much! Yes, I shall read “Prarabdha Karma After Self Realization” again (I already read it once before, but more deeply now).

LikeLike

Hello Brahmachari,

I hope you have gone through the three articles I mentioned. Please do not skip reading article 3, as it contains the answers to many of your questions. I forgot to add that my article “How Does A Jnani Person Deal With the Negative Impacts of the World: Part 1/2 – Titiksha” here https://neevselfinquiry.in/2020/11/16/how-does-a-jnani-person-deal-with-the-negative-impacts-of-the-world-part-1-2-titiksha/

shall provide further understanding.

Please do not hesitate to ask your questions if after reading these articles, any of your doubts remain.

LikeLike

Inspiring, lucid, detailed, penetrating! Thank you so much Anurag sir🙏

LikeLike

Thank you, Brahmachari. In case you have any questions at any point in your journey, please feel free to ask me.

LikeLike